PART 6 – AFTER BEING BANNED FROM CAMPUS: WHAT HAPPENED TO STUDENTS UNITED? WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

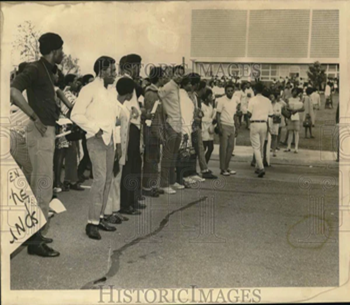

Picket lines and picket signs

Don’t punish me with brutality

Talk to me

So you can see

Oh, what’s going on

by C.C. Campbell-Rock

Imagine wanting to matriculate at a culturally woke college and a seat at the table where decisions are being made about your education. Now imagine being a Black student at a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) with 12 white overseers. That had been the situation in the Southern University system since its inception in 1880.

As the nation’s only historically black college system with five campuses in Louisiana’s three largest cities, Southern University and A&M College (SUBR) originally began in New Orleans, Louisiana. A group of black politicians, P.B.S. Pinchback, Theophile T. Allain, and Henry Demas petitioned the State Constitutional Convention in 1879 to establish an institution of higher learning for “colored people.”

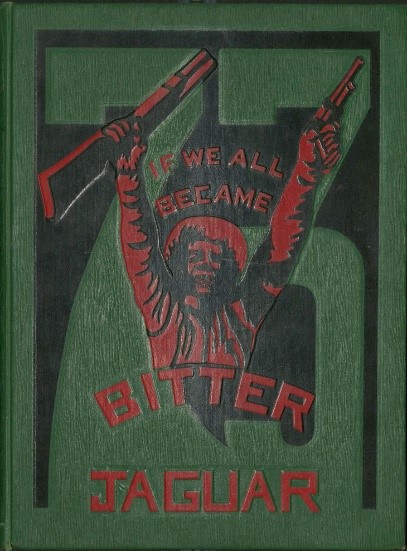

Fast forward to the 1960s and 1970s, Black students question the hypocrisy of a university promulgated by Black elected officials but ruled by Whites.

In the 1970s, Black students rebelled against a White power structure steeped in racism and plantation politics. The result was an unequal state university system where Louisiana’s Black state colleges and universities received far less money and resources than afforded the Louisiana State University system.

During the Black Liberation Movement, college students took ownership of their culture, neighborhoods, and communities. The SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) offered a template for “Black Power,” where Black youth fought for their political and constitutional rights. The Black Panther Party fed the Black community’s children, and the Kwanzaa tradition was in full force. Many renamed themselves, wore Afros and dashikis, and defined themselves.

Related: Part 5

Mainstream media called them militant. Instead they were merely throwing off the shackles of White oppression and organizing their collective power. Voter registration drives and political organizing conferences were designed for Blacks to win elected officers and further their goals of self-autonomy.

The modern Civil Rights Movement owes a debt of gratitude to those HBCU students who stood on the front lines of White resistance. They risked their lives to fight for their rights, abolish segregation, and determine their destinies.

Students United and the core group that organized the massive, month-long class boycott on Southern University campuses, wanted the university to reflect the values and culture of the student body:

“When we began to talk about Southern University moving to speak to the needs of the Black community, and when we started to question White people’s control over institutions populated by Black people, our questions raised some very fundamental issues that prompted forces of imperialism to try and suppress our movement by committing the brutal murders on November 16 (1972).

Therefore…it must be understood that the movement which began on October 16 has cut deep into the old White ruling class structure of racism and created the emergence of Black students saying that we will be the determining force that made and control our destiny because we recognize that we are an African people and that Southern University must restructure itself to speak to the needs of African people.”

“Support Our Struggle” – Documents of Students United

Southern University,

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1972-1973.

The campus-wide class boycott that began on October 16, 1972, ended in the senseless murders of Denver Smith and Leonard Brown on November 16, 1972, and expulsion and a lifetime ban of Students United’s organizers:

“Charlene Hardnett, also known as Sister Sakari Siti, Rickey Hill, also know as Malik Kambon, Nathaniel Howard, Herget Harris, also known as Sababu Thibika, Paul Shivers and Frederick Prejean, are hereby restrained, enjoined and prohibited from entering on the campus of Southern University in Baton Rouge, harassing other students or members of the faculty or in any manner disrupting or interfering with the operation of said educational institution.”

Judgment rendered Thursday, February 8, 1973, Nineteenth Judicial District Court, Civil Division F, Lewis S. Doherty, III Judge.

Ironically, the students who were banned from the campus were high-achieving honor students. They were juniors and seniors on the SUBR campus.

Still emotionally scarred from the events at SUBR to this day, the core organizers of the boycott graduated from other universities and charted careers influenced by the educational justice campaign they waged on SUBR’s campus.

Sukari Harnett remembers Governor Edwin Edwards taking the stand and recommending that she and fellow students be banned from campus for life. Hardnett, a New Orleans native, returned to the city and landed a job as a Pan-American Airlines flight attendant.

Related: Part 4

Hardnett got a letter from Andrew Billingsley, the provost of Howard University. “No one would accept us in Louisiana,” she explains. At Pan-Am, Hardnett experienced racism. The company wanted her to wear “white girl’s make-up and wanted to send her to South Africa. “They had just killed Steve Biko. They didn’t send Jewish girls to Arab countries,” she adds.

When Hardnett refused to go to Johannesburg, South Africa, the company fired her. Not one to tolerate injustice, Hardnett got Congressman Parren Mitchell to write a letter, and Pan-Am rehired her.

After graduating from Howard University, Hardnett earned a law degree from Antioch College and worked at New Orleans Legal Access Corporation. She left New Orleans and worked for Clarence Thomas in the Office of Appeals at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Hardnett was there when the Anita Hill controversy arose.

“As human beings, we all make mistakes,” Sukari Hardnett, who in 1991 submitted a sworn affidavit to the Senate Judiciary Committee testifying that she had been subject to Thomas’ “unpleasant” attention, told The Daily Beast.

“We were never called to testify,” Harnett told Think504. com. Despite accusations about Thomas’ unfitness, a Senate Committee led by then-Senator Joe Biden cleared the way for Thomas’ nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Hardnett initially planned to go to Southern to get a Ph.D. in psychology, but she got into law because her SUBR experience illustrated the need for progressive lawyers. Harnett later went into private practice and specialized in discrimination cases.

Related: Part 3

Hardnett says life after being banned from Southern University was hard. “It’s been a sacrifice and a struggle.” She left that campus with an arrest record and, along the way, lost a marriage. However, she became a living legend, mother to two and grandmother of one.

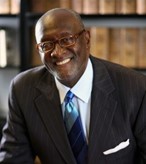

Rickey “Malik” Hill became a lifelong scholar, distinguished college professor, dean, political scientist, author, consultant, and civil rights lecturer. Dr. Rickey Hill’s 24-page Vitae documents his outstanding accomplishments, scholarly writings, awards, organizing, leadership, and lecturing skills. He taught and chaired political science departments at several HBCUs.

Like Harnett and others, Hill was arrested, expelled, and banned from SUBR. The Bogalusa native earned a full scholarship to Fisk University, a master’s degree, and a Ph.D. in political science from Clark Atlanta University.

Hill’s career goal was to get Black people to “retain our history.” Hill published over 50 journal articles and 50 general articles. He was a member of the South Carolina Archives and History Commission and a founding member of the South Carolina African American Heritage Council. Hill also traveled to several African countries in the 1970s to represent the African Liberation Support Committee/.

Hill is the retired Professor and Chairman of the Political Science Department at Jackson State University.

The political scientist continues to be concerned about ‘this black shit,’ as his critics called Black politics, political theories, and civil rights when he was a youth. Civil rights leaders in Bogalusa, a historic city in Louisiana’s Civil Rights Movement, influenced Hill.

The professor dedicated his life to ensuring that Black students learn African American history in college, an opportunity denied him at Southern University. There was no African American Studies Department when he attended SUBR.

“The Southern experience steeled me. It’s been a part of who I am. I never liked authority, but I wasn’t someone to rebel,” Hill said recently. He still believes substantive changes are needed at HBCUs in this country.

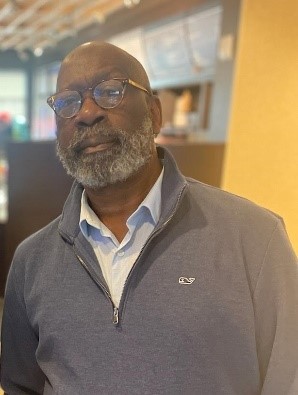

Herget “Sababu” Harris organized engineering department students in solidarity with the psychology students, where Hardnett launched Students United. The group didn’t have a single leader but a small group of organizers who called for and got other students involved in the campus-wide boycott.

Each department had a list of needs. The engineering department wanted more labs, better facilities, and more professors.

Harris was a high school honor student in Jennings, Louisiana. He earned an internship at Southern University and decided to study engineering there.

Harris was at the administration building on November 16. When he walked out, he was flanked by Smith and Brown. He saw them fall. “The brothers were not getting up.” It was thought that the sheriff’s deputies were aiming at Harris, the spokesperson for Students United. Smith and Brown were killed instead. Harris later turned himself in to avoid getting arrested.

Related: Part 2

After being expelled from SUBR, Harris worked three jobs and saved enough money to attend Howard University. He put his Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering to work at Bell Laboratories in Columbus, Ohio. To climb the ranks at Bell, Harris earned a master’s degree from the University of Michigan. He worked in the Bell system until retiring in 2016.

Nathaniel Howard is a native of Minden, Louisiana. Howard played basketball in high school, but his math skills propelled him to summer school at Yale University. Hill calls Howard a mathematical genius. “I could have gone to Yale, but I wanted to attend an HBCU. He chose Southern University.

Howard was arrested twice and expelled from SUBR for participating in Students United. He moved to New Orleans and worked in a psychiatric hospital before moving to Washington, D.C., hoping to attend Howard University.

When the university asked Howard to be on his best behavior (after the SUBR issue came up), Howard, who had a 4.0 in math, attended the University of the District of Columbia.

Howard worked for the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics for 42 years. During that time, Howard was a supervisor of mathematical statistics. He agrees with Hill that the Southern University system is still being short-changed by the state. “Even today, when you look at the per pupil allocation, you’ll see that LSU’s football team is getting as much money as the whole Southern University System.

Southern University in Baton Rouge was a turning point in his life. After Southern, Howard dedicated his life to service. He was active in education, community affairs, and the church.

The father of eight, was PTA president and vice-president of his children’s school, an organizer of a community festival for 30 years, and a lay minister.

As the parent representative on the D.C. Education Board of Trustees, Howard advocated for equity in funding at the district’s schools with predominate Black student bodies. “I was fighting for some of the same things we fought for at Southern. All these activities came from my experience at SUBR,” he explains.

Howard says his most significant memory of Southern University was meeting his wife. “I saw her, and God told me she was my wife. Regarding the 1972 killings of Smith and Brown, Howard wants the university to solve the murders. “For 50 years, they haven’t done anything.” He also thinks Southern should give scholarships to the families of the slain students.

Patrick “Ngwazi” Robinson was a member of Students United but wasn’t expelled. His father knew someone in the administration. “We pushed to have a Board of Supervisors for the Southern University system,” he explained.

An honor student, Robinson earned his bachelor’s degree in political science from Southern in three years and a law degree from Southern University Law School. He didn’t practice law but went to work at the Baton Rouge Advocate. After leaving the Advocate, Robinson began writing about Black history events.

“That was a stressful thing at Southern. I developed anxiety and panic attacks and depression,” Robinson remembers.

Ola Sims Prejean and Fredrick James Prejean Sr. were college sweethearts. They were attending Southern University at Baton Rouge during the campus upheaval. Ola was a psychology major, and Fred was an accounting major.

Fred’s attendance at the March on Washington in 1963, when he was 17, inspired him to become a civil rights activist. Fred became an organizer for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, and the Congress of Racial Equality.

After serving in the Marine Corps Reserve, Fred worked at Southern Consumers Cooperative, where he helped black entrepreneurs envision, design, and launch startup businesses.

He joined the group when Ola invited him to a Students United meeting. He was arrested on November 16, 1972.

Ola was suspended, and Fred was expelled and banned from the campus. Fred transferred to Xavier University, retained an attorney, won his case, and was allowed back on the SUBR campus. Ola graduated in 1973, and Fred graduated in 1974.

Ola earned a master’s degree in educational psychology from Howard University and worked as a school psychologist in Lafayette Parish. Fred attended the University of Washington and the Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy at Duke University.

In 1976, Fred founded Empire Management, Inc., a business resource, research, and development consulting firm. His career highlights include work for the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, Lafayette Southern Consumers Cooperative, Greater Southwest LA Black Chamber of Commerce, Louisiana State Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, and the Urban League.

MTM conducted a successful campaign to remove the Jim Crow Confederate Gen. Alfred Mouton statue from downtown Lafayette. The statue was removed in July 2021.

In 2016, Fred became the founder and president of Move the Mindset (MTM), a non-profit educational advocacy and community development organization committed to addressing discrimination, civil rights, and other human rights disparities in the city and parish of Lafayette.

“There are gaps in my memory about that day,” Ola admits. “I’d like to see the SU Board use its power to act on the priorities Students United asked for,” Ola comments.

Ola and Fred married in 1974 and remained together until his death in January 2022. Before he passed, Fred gathered data on Southern University for a documentary film. They have a son and two grandchildren.

Chester Stevens experienced a “break in belonging” at LSU. He and other Black students were racially profiled and discriminated against at the state’s flagship university. He switched to Southern University in Baton Rouge, where he planned to earn an electrical engineering degree.

Stevens said he was arrested, interrogated, beaten, and maced for no good reason. He wasn’t banned from campus but was told he couldn’t graduate two to three weeks before graduation.

His math teacher intervened and said he couldn’t march across the state but that they would mail his diploma to him.

“I’m still traumatized and still angry,” Stevens said about the tragedy on SUBR’s campus.

The Baton Rouge native moved to California and worked for IBM. He holds two technology patents.

Stevens also played jazz in California. He worked in engineering and taught school. Stevens taught STEM classes, band, choir, English, and Chemistry in Hercules, California. He is the divorced father of one child.

After 45 years, Stevens moved back to Baton Rouge to care for his 93-year-old mother. He is pioneering c a new genre of pocket-sized books. His 25-page fiction series is about a character named Joshua. Titles include “High Tech Blues,” “Walk to Torichis,” and “Ola’s Strip Joint.”

Brenda Brent Williams arranged a phone reunion of the student protesters last fall. “Most of us hadn’t talked about 1972. Some had a lot of suppressed emotions,” the Baton Rouge native said.

Williams was in the honors program at SUBR. She was studying sociology. She would have graduated in December 1972 had the campus been open.

Williams was standing in front of the administration building when Smith and Brown were killed. “I was always leaning toward social justice, but that incident heightened my interest,” she explained. She graduated from SUBR in January 1973.

Williams retired from the Social Security Administration after 33 years of service and settled in Gretna, Louisiana.

Today Williams coordinates St. Joseph the Worker Catholic Church’s social justice campaign for foster youth and volunteers with VOTE (Voices of the Experienced). The Gretna resident is also a Jefferson Parish Children’s Youth Board member. She is the mother of two and grandmother of three. Listen to the podcast of Williams and Hardnett here.

Several Students United members attended a Commemorative event where official apologies and acknowledgments were offered by Southern University officials, Mayor Sharon Weston Broome, and Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards at the Old State Capitol on November 16, 2022, on the 50th Anniversary of the SUBR Tragedy. The event was jointly hosted by the Louisiana State NAACP Conference President Michael McClanahan, Professor Angela Allen-Bell, Esq., and her Civil Rights, Law & Racism students. See the Video here:

| 50th Anniversary of the Deaths of SU Students Denver Smith and Leonard Brown – A Cold Investigation: Episode 50 www.youtube.com |