THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF A CAMPUS TRAGEDY

PART 2: Students United Share Eyewitness Accounts of Police Brutality and Murder on an HBCU Campus

There was something very wrong on the Southern University campus in Baton Rouge in November 1972.

Southern University (SU) students formed a coalition called “Students United’. They demanded better facilities, healthy food, an Afrocentric curriculum, progressive professors, shared resources with the Scotlandville community, and a voice in decision making. They also wanted the Southern University system to have its own Board of Supervisors. Finally they presented a list of grievances to University President George Leon Netterville, but their requests were denied.

In 1972, at the height of the Black Power and Black Liberation Movement, thousands of SU students continued the nonviolent civil rights protests launched by college students in the 1960s and early 1970s. At that time, Southern University was the largest HBCU in the nation, with at least 10,000 students.

Black college students joined the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), CORE, SCLC, and the NAACP. They marched and protested for voting rights, equal opportunity, and an end to de facto segregation. Still other students engaged in boycotts on college campuses to effect change.

In 1970, four students were killed at Kent State University in Ohio on May 4. And two others were gunned down at Jackson State University on May 15 while protesting the Vietnam War.

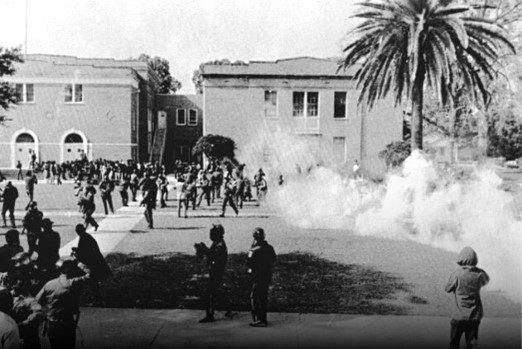

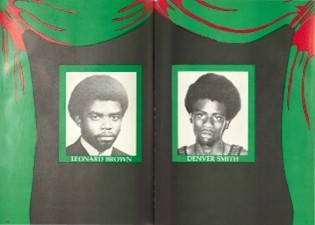

On November 16, 1972, to disperse student boycotters at Southern University’s Baton Rouge campus, police opened fire and killed Denver Smith and Leonard Brown.

Related: 50th Anniversary of a Non-Violent Movement

Students United at Southern University’s Baton Rouge campus refused to be educated at an HBCU run by 12 white males on the State Board of Education. They decided to take direct action. They would boycott classes until the administration heard their concerns and negotiated with them.

Several students were among the core group that organized the class boycott. According to interviews conducted with Students United organizers, they were all leaders.

Among those who bravely stepped up to negotiate change were Charlene ”Sukari” Hardnett, who launched the organizing effort in the Psychology Department, Herget “Sababu” Harris, Ricky “Malik” Hill, and Nathaniel Howard. Others joined the boycott, including Frederick Prejean, Ola Sims (who later married Fred), Brenda Brent, Patrick Ngwazi Robinson, and Chester Stevens.

Students Share Eyewitness Accounts

These are their stories:

Sukari Hardnett

The resignation of Charles Waddell, the new chair of the psychology department sparked the boycott. According to Hardnett, Waddell left after requesting better resources and not getting them. He was a progressive educator who supported the students’ desire to reach out and provide mental health services to the Scotlandville community.

Other professors also resigned due to the lack of facilities and equipment to fully prepare students for careers in psychology, engineering, social sciences, and other fields.

Sukari was a member of the honor society and the president of the Psychology Club at SU. She transferred from LSU to Southern because “I had problems with racist instructors,” she explained.

Before the 1972 boycott, Sukari organized a protest at a theater that allowed children to see X-rated movies. The theater was dirty and unkempt, and the owners kept the exit doors locked. “It was a black business being exploitive,” she adds. “We prevailed and kept children out of X-rated movies. They cleaned up the theater and unbarred the exit doors.”

As a result of that experience, Sukari learned that peaceful protests and direct action could create positive change. She began organizing fellow students to address the loss of qualified, progressive professors after seeing that nepotism led to hiring unqualified professors who had relatives in the administration.

“When we saw the conditions of the dorms and the food, and that students were not getting the academic support they needed to advance, more students joined the boycott to address those issues,” Sukari continued.

Students Share Eyewitness Accounts

“We wanted the university to be more Afrocentric and teach students about their civic duties,” she said. Southern had resources to help Scotlandville where “conditions were terrible. What the university was doing was “preparing students to perpetuate racism.”

Students from the psychology, engineering, social sciences, and other departments joined the class boycott, which began on October 16,1972. At one point, nearly 99 percent of the student body met in the men’s gym for daily updates from Students United organizers before campus officials blocked them from using the facility. Undeterred

“We were civilly disobedient,” says Sukari. The students enacted the nonviolent protest steps initiated by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the SCLC.

“In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action,” King wrote in his Letter From A Birmingham Jail.

“You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches, and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such tension that a community that has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored,”

And that’s precisely what Students United did.

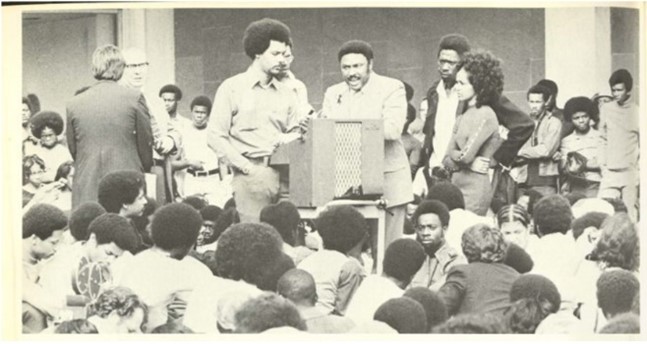

They presented their grievances to Southern University, President G. Leon Netterville, marched seven miles to the State Board of Education and marched to the Louisiana Capitol to petition Governor Edwin Edwards to act on their grievances.

Related: 50th Anniversary of Student Murders on Campus

Netterville refused to negotiate in good faith. He listened to the students’ demands but refused their requests. The State Board of Education had initially declined a meeting with the students. However, Jesse N. Stone, Jr., Esq., the Assistant Superintendent of Education, met with Students United.

“We had a good heart. We wanted to do right for our people,” Sukari said. At 4 am, there was a knock on her door. It was the police with a warrant for her arrest in the pre-dawn hours of November 16, 1972. Sukari was in jail when she heard about the campus unrest and that Smith and Brown were killed. ‘I felt impotent. I couldn’t do anything but listen to the radio. The sheriff refused to set bail. I heard that students went to the administration building to meet Netterville and tell him to get us out of jail. We never heard from him.”

Police arrested Fred Prejean and Lewis J. Anthony Sr. that morning. Sheriffs tried to arrest Herget “Sababu” Harris, but he wasn’t home. The students were charged with inciting a riot and interfering in the educational process.

Students United members met virtually for the first time in 50 years: Video

Next Week: THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF A CAMPUS TRAGEDY Part 3 –Students United – Phoenix Rising Victories