Southern University Students in New Orleans Started It: Black Student Protest Movement and Civil Rights Movement

By C.C. Campbell-Rock

Southern University students figure prominently in the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Student Protest Movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Black Liberation Movement was in high gear. Black students at Swarthmore College, University of North Carolina, Brown University, Duke University, University Wisconsin-Madison, Concordia University in Canada, Harvard University, University of Georgia, and City College in New York made demands for Black studies, more Black professors, and an end to discriminatory treatment on campus.

However, Southern University students in Baton Rouge (SUBR) and New Orleans (SUNO) protested on and off campus. They boycotted classes at both campuses for black history studies and better libraries, facilities, food, and housing. Their top priority was a seat at the table where decisions are made.

Off-campus, the students joined the Civil Rights Movement, freedom rides, and marched against segregation and economic injustice. They rallied against the Board of Education, which oversaw the HBCU. Comprised of 12 white men, the education board allotted more taxpayer money and resources to the Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge than the entire Southern University system.

More than a decade before the horrendous 1972 shooting deaths of Denver Smith and Leonard Brown at Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge by police, students fearlessly put their lives on the line to end segregation and economic injustice.

Brown v Board of Education struck down segregation in 1954. But Louisiana is one of the southern states that was forced to integrate.

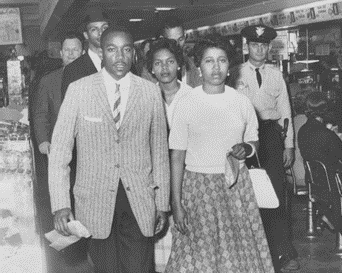

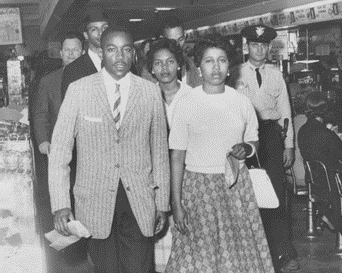

On March 28, 1960, Southern’s Baton Rouge students sat at the S.H. Kress’s lunch counter. The next day they sat down at lunch counters at Sitman’s Drugstore and the Greyhound Bus Terminal. They boycotted local businesses over their discriminatory hiring practices.

“After ordering the students to leave, police arrested and charged them with disturbing the peace and claimed that their behavior could “foreseeably disturb or alarm the public,” according to Louisiana’s “disturbing the peace statute,” according to the U.S. Civil Rights Trail website.

Marvin E. Robinson was student government president and All-American track-and-field athlete during the early 1960s. He kept students informed about negotiations and organized the class boycott. And he was a founding member of the historic Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), field secretary of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and a Freedom rider. He was jailed and beaten several times during sit-ins. Robinson was on the bus with other Freedom riders when they were attacked, and their bus burned.

Robinson was expelled 28 days before graduating and ordered to leave the state of Louisiana by Governor Jimmy Davis. He ultimately earned a law degree from Howard University in Washington D. C. He eventually became an entrepreneur and a mentor.

On April 4, 1960, SUBR students began boycotting classes in solidarity with the arrested students. “They rallied and withdrew from the campus,” historian and author Dr. V.P. Franklin explains.

Garner v. Louisiana was a landmark case resulting from the students’ arrest. Thurgood Marshall argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court. On December 11, 1961, the court unanimously ruled that Louisiana could not convict peaceful sit-in protesters who refused to leave dining establishments under the state’s disturbing peace laws.

Obviously, the federal ruling meant nothing to Louisiana lawmakers because Louisiana police arrested students involved in the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) March to the Louisiana State Capitol on December 15, 1961. Ronnie Moore, chairman of CORE’s Baton Rouge Chapter, organized the March. See the video and coverage of the December 15, 1961 event by USA Today here.

“They were attacked, arrested by police, and expelled,” adds Franklin. “Southern is a state school, so pressure was put on Felton to punish the students.”

Felton G. Clark was the second president of the Southern University system. He succeeded his father, Joseph S. Clark.

When classes resumed on January 25, 1962, SUBR student, D’Army Bailey gave a stirring speech and rallied the students to boycott classes. He was expelled from the university.

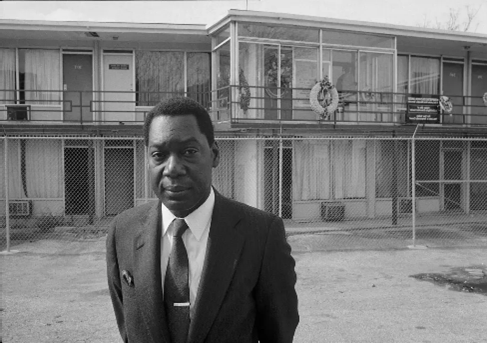

Bailey eventually graduated from Clark University and Yale University. He was a lawyer, circuit court judge, civil rights activist, author, and film actor. He also served as a city councilman in Berkeley, California, from 1971-73. In 1991, Bailey founded The National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel location where Dr. King was assassinated.

SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY IN NEW ORLEANS STUDENTS TAKE TO THEIR PROTEST TO ANOTHER LEVEL

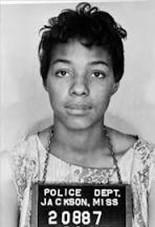

Student activism was alive and well on Southern University’s New Orleans campus in the 1960s. Oretha Castle, who married CORE leader Richard Haley, Rudy Lombard, a Xavier University student, Tulane student Sydney L. Goldfinch Jr., and Cecil Carter Jr. of Dillard were arrested on September 17, 1960, and convicted of criminal mischief for sitting at the McCrory’s lunch counter on Canal Street. The U.S. Supreme Court vindicated them and overturned state and lower federal court convictions in Lombard v Louisiana in May 1963.

Doris Castle, Oretha Castle Haley’s younger sister, was also a SUNO student and CORE member. Jerome “Big Duck” Smith, another SUNO student, was a CORE Field Secretary. Oretha Castle Haley would become the administrator of Charity Hospital, run political campaigns, and establish The Learning Center, an early childhood facility. Smith founded the Tambourine and Fan Club and oversaw the building and operation of The Tremé Community Center.

Toward the end of the sixties, Southern students continued to protest and call for black history to be included in the curriculum and the hiring of more Black professors.

Still, 1969 proved to be a flashpoint for student activism on SUNO’s campus.

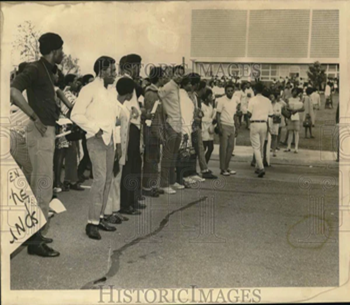

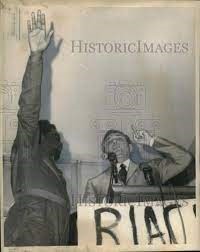

In 1969 SUNO students replaced the American flag with a Black Liberation Flag. They also took over the administration of the school. Classes continued, and students staffed the administration offices. When police arrested 20 students, a class boycott followed.

Kalamu ya Salaam enrolled at SUNO after serving in the U.S. Army. He was the spokesperson for the group of students demanding change.

Salaam said the students’ primary motivation for protesting in 1969 was the “significant needs at SUNO.”

“We had a brand new library building with no guts. We used to joke that high schools had more books than our library.” They also wanted a Black studies department.

“We used humor and sarcasm” to make a case for positive change. “Whenever it rained, the grounds would flood because the site was not landscaped. If the water stayed for a while, crawfish would grow.

“After a hard rain, we’d be sitting out in lawn chairs eating crawfish.” Salaam said student protesters had a hand-written sign that illustrated the sarcasm of their demonstrations: “Dem bad niggas done done it again.” It was not just political; it was our calling card.”

Their demonstrations had statewide ramifications. The students knew the changes they wanted required legislative actions and the governor’s signature.

Salaam remembers the day students forced Governor John McKeithen to come to SUNO. The governor had vowed not to go to SUNO during the demonstrations.

“Before he finished talking, we had 500 students blocking the exits. Some say we kidnapped the governor. Some call what we did a Mexican stand-off.”

After negotiating, McKeithen agreed to go to SUNO. Salaam rode in the back seat next to the governor’s bodyguard. With the cafeteria packed with students and the media recording him, McKeithen promised to make changes.

McKeithen had called the National Guard out to the campus on April 9, 1969, when the students replaced the American flag with the Black Liberation Flag.

Criminal charges filed against Salaam and other students in the Afro-American Society of SUNO for desecrating the flag were both unfair and unnecessary.

“When our veterans took the Stars and Stripes down, they gave it a military fold,” Salaam explains. Then they gave it to campus security and replaced it with the Black Liberation Flag.

“The flag was flying when the National Guard and police came on campus. “One professor came out and asked, ‘Where’s the real flag,’“ Salaam recalls.

“They (National Guard) started beating us. They had the paddy wagons lined up. And they had to force me into the paddy wagon. And that was my first experience with mace. They hit Sandra Marcelin across her head,” Salaam continued.

Sandra Marcelin Ewell wasn’t a SUNO student. She had come to the campus to support her brother, Allen Marcelin. “They (police) knocked out his beautiful, pearly white teeth. Then they started beating me on my head. They put us all on the bus and took us to jail.,” Ewell remembers.

“We both had to go to Charity Hospital. I had to get ten stitches. I still have the scar.” Ewell says. Her brother’s teeth are still damaged. Ewell lost her job after her picture appeared on the front pages of the Times-Picayune and The Final Call.

Looking back, Ewell says being terminated from Travelers Insurance Company was a blessing. She became a real estate developer. “I’m in my 13th house now.” Currently, Ewell teaches sewing at several NORD facilities. Her brother Allen played semi-pro football before becoming a construction contractor.

IN 1969, SUNO students Lynn D. French, David C. Humbles, III; Keith W. Medley, Vallery Ferdinand III. (aka Kalamu ya Salaam), Lawrence J. Terrel, Edward Merricks, Spencer Williams, Gray Brown, Larry Jones, and Blake L. Porter sued SUNO Dean Emmett W. Bashful and Southern University President G. Leon Netterville for expelling some of them and suspending others. They wanted to be reinstated in good standing at the university.

They were expelled and suspended for “allegedly taking over the administration building.” But they didn’t win the lawsuit.

“They expelled over 3,000 students over the summer,” Salaam adds.

Kalamu ya Salaam unsuccessfully sued District Jim Attorney Garrison and Police Superintendent Joseph I. Giarrusso for bringing criminal charges against SUNO students for “desecration of the American flag.”

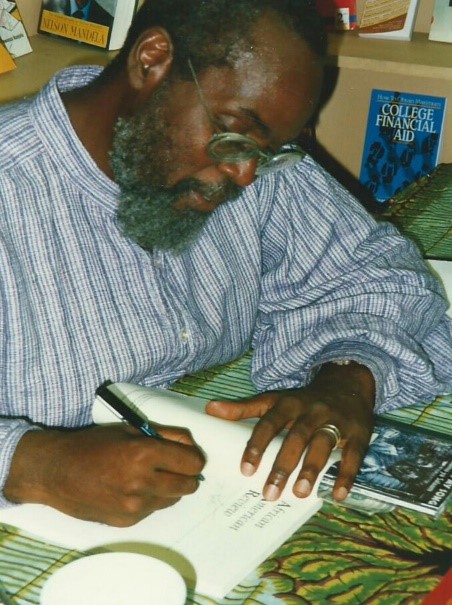

Kalamu ya Salaam later became the editor of The Black Collegian Magazine. He is a noted poet, author, educator, and historian.

Next Week: 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF A CAMPUS TRAGEDY

PART 6 – WHERE ARE THE STUDENT PROTEST LEADERS NOW?

C.C. Campbell-Rock © 2022 – All Rights Reserved

Great writing we need this and more historical stories told daily ,because our community need to know what our people have endured and take up the fight , not fight each other and we got to stand up for US

Starting with ECONOMICS stop supporting others

Looking forward for next week

As a witness to the aftermath of the flag replacement incident at SUNO in 1969, I can attest to the facts reported by Kalamuu. Although I had recently moved to New Orleans about a year before the incident, the political climate was such that it was almost palpable among the Black students on that New Orleans campus of Southern University. I have been married to one of the major players in this article, one Allen Jules Marcelin since 1971 (we were dating in 1969 when the aforementioned incident took place), and I can remember his being so committed to the struggles Black students were facing in those days. In fact, to this day, he continues the struggle on behalf of our people, both here at home and the African diaspora.