STUDENTS UNITED’S FOOT SOLDIERS BEAR WITNESS

By C.C. Campbell-Rock

“Southern University can become the political, economic, and social base that is needed to develop the Black community and move itself out of its present status of being a racist institution controlled by capitalist and imperialists forces.” Students United

Southern University and A&M College has been located in Scotlandville since 1914. From a small school of 500 students through 1938, in the post-World War II era, it expanded to 10,000 students by the late 1960s and through the 1990s. From the beginning, the presence of the college stimulated related businesses and encouraged more blacks to settle in the area, including faculty and staff. This became the largest black-majority community in the state before World War II.

In 1970, Blacks comprised 91.8 percent of Scotlandville’s 22,557 population, of which 10,000 attended or worked at Southern University. The median income of “Negro families” in the U.S. in 1972 was $6,440 compared to the $11,550 for whites, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Poverty was a significant issue in Scotlandville, so students on Southern University’s Baton Rouge campus organized Student United to use the university’s resources to help Scotlandville residents. They aimed to help the community mirror the Black Panthers’ community service programs.

The students also wanted improvements to campus facilities, a better library, resources for their respective departments, and a Black Studies Department. The university’s “inadequate facilities, inept administrators, and poor student services” were intolerable.

“There are various kinds of resources that can be used for the betterment of the Black community. For instance, Southern University’s Dairy can distribute milk into the community.” Students United wrote in its ‘Support Our Struggle” pamphlet.

The students wanted the Agricultural Department to establish training programs to help develop scientific farming to feed the people. The architecture and Industrial Arts Department could design and build various kinds of housing complexes to help correct housing problems. The university’s Political Science Department could organize seminars for political education. The Psychology Department could offer mental health services to the people.

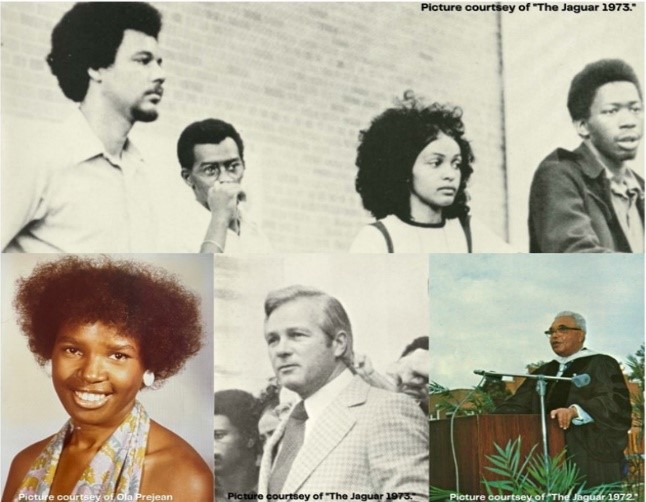

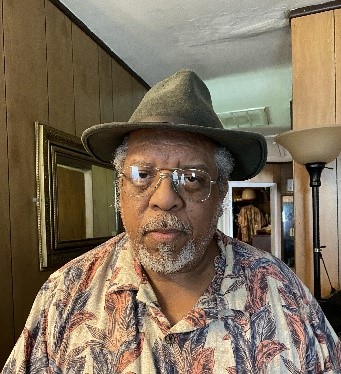

Frederick Prejean, Ola Sims, Brenda Brent Williams, Patrick “Ngwazi” Robinson Jr., and Chester Stevens joined Students United after learning about the group’s mission to have a voice in decision-making at Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge (SUBR).

Back then, the Black Liberation Movement was in full force across the U.S. Black youth were taking control of their own identities, renaming themselves with “free” names that embraced their ancestral roots and Black culture and each other. It was common to hear young Black adults address each other as brother or sister. The Impressions’ song Choice of Colors, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On,” and James Brown’s Say It Loud, I’m Black And I’m Proud thoroughly explained the Black experience and black identity fueling the Black Liberation Movement of the 1970s.

These are the stories of the foot soldiers of Students United:

The administration was tying his hands,” Ola Sims, a psychology major during that time, says of Dr. Charles Waddell, the Psychology Department’s chair. The young professor brought energy and fresh ideas to the department, but the administration would not provide the resources he needed for the hands-on field experiences students required.

“He was too progressive from the administration’s point of view. Waddell’s resignation angered the students. “We were losing someone we were connected to, and things were going on in the Scotlandville community that the students were involved in,” Ola remembers. Psychology students provided mental health treatments in the community and at St. Gabriel’s women’s prison.

“It grew from there,” Ola says, noting that the student movement began in the psychology department. Charlene “Sukari” Hardnett’s idea was to organize the students to take action. She was also a psychology major.

Ola was not among the core organizers of the ensuing boycott and protest march. Still, after inviting “Fred” Prejean, her fiancé, to one meeting, he joined the initial organizers and helped launch the campus movement.

“Sukari knew Sababu and Rickey,” Ola adds. “It became clear that there were concerns across all departments, and students wanted a seat at the table, but not at the table of the white political structure over SUBR.

“There was no African-American Studies Department. People in the Political Science Department spoke about the need for Black history courses. That was one concern.,” she adds.

He was all in when Ola invited her fiancé Fred to a meeting. Fred was an accounting major. Ola lived on campus. On November 16, 1972, the day students were tear-gassed and Smith and Leonard were killed, Ola went to the administration building with students to appeal to President Netterville to get the students released from jail. Fred had been arrested during the pre-dawn hours of the morning, along with Sukari, Paul Shivers, and Louis Anthony.

“I recall him telling us to wait.,” she recalls. But she didn’t wait. She followed Netterville to the State Board of Education. Ola didn’t see the murders of Smith and Brown allegedly at the hands of an East Baton Rouge Sheriff’s deputy.

“I was horrified at their deaths, and Fred was devastated. He was afraid I had been killed. I was hurt, angry, and mad that this had happened. This had been a peaceful demonstration that didn’t warrant this type of response. Ola was suspended and on probation, and Fred was expelled and banned from the campus.

Fred passed away on January 27, 2022.

Speaking for her husband of 48 years, Ola says, “He was a community organizer and civil rights advocate. Civil rights ran through the fabric of his being.” Fred worked with the SNCC and CORE and attended the March on Washington in 1963 at age 17. The Lafayette native’s family was involved in civil rights and politics. His brother was one of the first Blacks to run for political office.

Patrick Ngwazi Robinson, Jr. credits God for him not getting banned, arrested, or killed at SUBR. The political science major says his father had a contact at the university.

“The powers that be wanted to victimize and blame the students, but Students United always worked from a position of non-violence and didn’t endorse the destruction of people or property.

The administration was told Ngawzi was attending class, but he wasn’t. “I was a part of Students United. We wanted to make the school a better place for black students. Southern was sorely lacking in black history classes. We also pushed to have a board for Southern University in Baton Rouge and

Figure 1 Patrick “Ngwazi’ Robinson Jr.

students on the board to have a voice,” Ngwazi explains.

Many young Black adults in the 1970s chose “free” names relative to Africa. Patrick chose “Ngwazi” as his free name. It was the name of a government official in Ghana. He mentioned Amir Baraka, Hakeem Matabutu, Muhammad Ali, and Stokely Carmichael Carmichael, who changed his name to Kwame Ture and coined the phrase “Black Power,” and others who chose to adopt names of their own choosing instead of their “government” names.

A ”self-appointed” historian, Ngwazi remembers the campus upheavals at South Carolina State College in 1968, where three black students were killed, and in 1970, at Kent State, where four students were killed, and Jackson State where two students were “killed by police firing into a dormitory.” The Vietnam War spawned a nationwide social upheaval, and the Black Panthers and other organizations demanded change.”

That was the climate in which Southern University students lived. Ngwazi was with the contingency of students who went to Netterville’s office on November 16 to ask him to get their fellow students out of jail. “Netterville said to come in. Sit down. Don’t go anywhere, stay here. One by one, the secretaries left after receiving calls.”

Ngwazi said he looked out the window and saw “an eight feet tall paddy wagon.” He heard sounds coming from a bullhorn, but the students didn’t understand what was being said. Tear gas canisters were thrown into the administration building. “Tear gas is no joke. It can burn.”

Ngwazi says he saw a “policeman throw a student down and use the butt of a gun against the student’s head. Students around him went into the ravine, and when they reached the water’s edge (Lake Kernan), they wadded across.

When Ngwazi headed toward the back of the Student Union, he said a male dressed in Black went across the street and threw something into the Registrar’s Office. The building went up in flames. Helicopters circled the campus ordering students to leave the campus. Ngwazi decided to go home to Monroe, Louisiana.

He was a member of the Blackstone Society, a social group of students majoring in law, political science, and engineering. Ngwazi says members of the psychology club came to the Blackstone Society to get help with a problem. A white professor had touched a Black student on her behind as she walked out of class. That was another rallying point for the boycott.

Ngwazi was one of the students who went to other classes asking students to join the boycott. Before the November 16, 1972, incident, 90 percent of the students had joined the movement for student rights.

When Brenda Brent Williams graduated from McKinley High School in Baton Rouge, the salutatorian received scholarship offers from LSU and SUBR. Although she lived closer to LSU, she didn’t want to go there “because of the school’s reputation about the treatment of people who looked like me.

Two of Brenda’s siblings had attended Southern, and she wanted to be a part of the Black experience, so the honor student started at Southern in August 1969. Also Brenda was a senior and would have graduated in December 1972 if the campus hadn’t been shut down after the boycott.

Brenda was a sociology major. She attended the Students United meetings. “I was more of a listener and observer,” she says. “I had my suspicions that some infiltrators were on campus.” Nonetheless, she was in front of the administration building on November 16, 1972. She ran toward the ravine but saw one of the murdered students fall.

“The ravine ended at the river. I didn’t know students got killed until later. And I was in shock. I went to Denver’s funeral. “The most traumatic thing is that it was said his lips were shot off.”

Brenda felt bitter and angry when looking at “Big Bertha,” an old military tank. She wondered if the campus was a war zone. “It bothered me that it was reported we had weapons.” Brenda saw the Registrar’s Office burning. The damage to the buildings was done by the officers,” she said.

“I got involved because I wanted to see a change in the Social Science Department. “And I always leaned toward social justice, but that incident heightened my interest.”

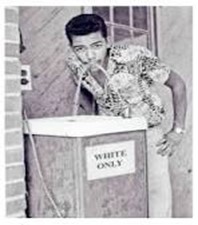

“I just did not like injustice from an early age,” she continues. As a child, Brenda wanted to be on the Romper Room, a television show for young children. My Mom told me I couldn’t be on the show because I was a Negro or colored. Brenda recalls not being allowed to go into the “Whites Only” bathroom or drink from the water cooler marked White.

– circa 1964 – Photo Courtesy Cecil Williams

“The water coming from the ‘colored’ water fountain was cool. By that time the signs were supposed to be down,” Brenda says. So, she went into the “White” bathroom anyway. She attended all Black schools and never had a White teacher until she got to Southern.

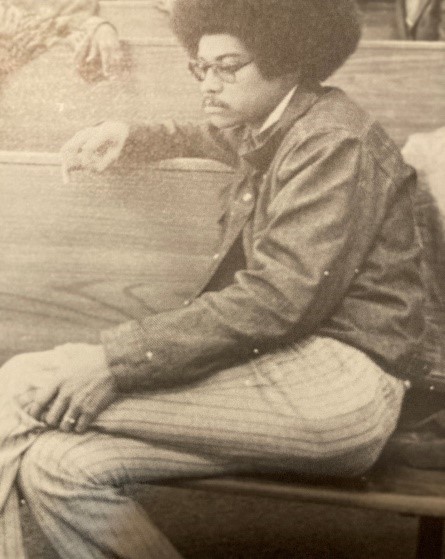

Chester Stevens, a native of Baton Rouge, chose to go to LSU. He was a chemical engineering major. He met David Duke there. Chester played alto sax in LSU’s marching band but was told he couldn’t march or travel with the band because when the camera panned, a black face would destroy the homogeneity of the band.

Chester experienced several incidents of what he calls a break in belonging,’ brought on by racists who made Black people feel like they don’t belong in certain places. He remembers the first time he experienced “a break in belonging.” Chester could not go to an amusement park opening because they wouldn’t let “coloreds in.” He was six years old.

At LSU, when a black football player’s leg broke, the band (350 strong) cheered, ‘Kill the nigger, kill the nigger.’ “That was it for me,” Chester recalls. While at LSU, he heard that Southern University students were coming to the Board of Education. When they arrived there and stepped out of the elevator, they were surrounded by 14 officers.

The meeting had been canceled, and the cop told us we had failed to disperse and accused us of hiding in the building. The cop told us to run, but we refused. So, they took us to jail. When he got out on his own recognizance, Chester enrolled at Southern.

Chester was in an engineering class at Southern when Sukari walked in. “She burst into tears because instructors she cared about were being summarily dismissed. I went to the meeting. I wanted to be a part of it. And I felt it (injustice) deeply.

circa 1972

On the day of the murders, Chester was in the Administration building. “Nate was talking to Netterville about getting the arrested students released. I got in my car and went to the Board of Education meeting Netterville was attending. Then I turned on the radio and heard two students were killed. I knew they were standing near Sababu.”

The incident left him depressed and unable to go to classes. Chester wasn’t banned from campus, but two weeks before graduation, a professor told him he couldn’t graduate. “I went to talk to Dr. Crawford, my math teacher. He said I could graduate but I couldn’t march across the stage and that my diploma would be mailed to me.”

The lives of the banned students were totally disrupted. The incident was and still is traumatic for those who experienced the injustice wrought by SUBR administrators and law enforcement.

Next Week: 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF A CAMPUS TRAGEDY

PART 5 – SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY IN NEW ORLEANS STUDENTS STARTED IT!