Part 3 –Phoenix Rising: Malik, Nate, Sababu & Students United Face Jail & Prosecution

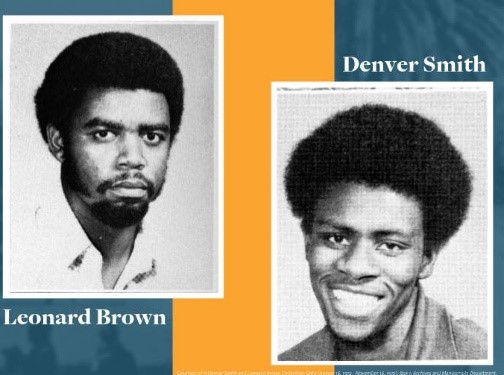

During the Students United class boycott, the administration at Southern University’s Baton Rouge campus was so determined to stop student protesters police were called to the Historically Black College & University (HCBU) several times. The needless calls ended on November 16, 1972, when two students were gunned down in a cloud of tear gas. They were in front of the administration building when tear gas canisters sent students running north, south, and east. They fell to the ground. According to reports, Brown died on the spot, and Smith passed 25 minutes later at an area hospital. The 20-year- old Black men were looking forward to graduation.

The officers who killed the students were never indicted, tried, much less convicted. The murder of Smith and Denver is now a 50-year-old cold case that is purportedly reopened.

The administration targeted the group’s organizers, and warrants were sworn out for their arrests. Some students who were perceived organizers of the boycott weren’t but were swept up into the insanity of arrests and bans and became felons for exercising their First Amendment rights.

Did the students cut classes? Yes. Did they flow onto a football field to boycott the game? Yes. But for trying to get an education that included black history and necessary equipment, housing, inclusion in decision-making, and the opportunity to share resources with the Scotlandville community, the students were vilified, ostracized, and banned from campus for life.

These are their stories:

“We were definitely conscious and definitely not just a few disgruntled students. We were rebels,” said Dr. Rickey “Malik” Hill, a political science major at Southern University in Baton Rouge.

He grew up in Bogalusa, Louisiana, in Washington Parish “when Black wasn’t considered beautiful.”

When Hill attended high school in the late 1960s, public schools in Bogalusa were still segregated, even though the Brown v Board of Education Supreme Court decision outlawed segregation in 1954. Following the decision, the state legislature banned the NAACP, and the Ku Klux Klan was a constant presence.

Malik was a high school scholar and destined to become a leader. He was the co-president of the student government association. Considered o of the highest-achieving students from across the state, Malik was accepted into Loyola University. He decided not to attend Loyola. He applied t Southern instead.

Students Face Jail

“I had already made up my mind to be a political science major. I grew up wanting to know why Black people were treated the way they were.” Malik was determined to get a doctorate in political science. His mantra was, “Stay in school, get an education. They can’t take that away from you.”

Malik met several like-minded young adults who formed the core organizers of Students United, including Nathaniel Howard.

Nate Howard is a “mathematical genius,” Malik said. Like Malik and other Black students in the 1970s, Nate identified with the Black Power Movement. It was a time when Black students defied assumptions that Blacks had to be “good Negroes,” Charlene “Sukari” Hardnett said.

They came of age when there was a raging debate over whether Black people should call themselves. Afro-Americans, African-Americans, or Blacks. Stokely Carmichael’s (Kwame Touré) mantra, Black Power, the Black Panthers’ self-defense organization, and James Brown’s ‘Say It Loud. I’m Black and I’m Proud’ settled the question for young adults in the 1970s.

Nate Howard, a native of Minden, Louisiana, was an honor student at Webster High School. A tall, slender man, Nate played basketball, but his goal was to earn a doctorate in mathematics. He was an honor student who spent summers in co-op study opportunities at prestigious companies and Yale University, which offered Nate a scholarship.

Like Malik, Nate experienced racism up close and personal. Minden schools were segregated. During his senior year at Webster High School, the government “removed all of our teachers” and replaced them with all White teachers. “We told them, ‘You’re not going to teach us. We’ll teach ourselves.’ Minden High School was predominately White. The government closed Webster High School and turned it into a Junior High School.

“I could have gone to Yale, but I wanted to go to an HBCU. I chose Southern over Yale, Harvard, and Grambling,” Nate said. Two of his math teachers from high school taught at Southern. They looked out for him. During his first year at Southern, Nate had an internship at the Aerojet Nuclear Atomic Energy Program. Also, Nate became Southern’s Student Government Association (SGA) president.

Nate says he was attracted to the Blackstone Society because of the students’ petition to divest in South Africa. The numbers man also had issues with the disparities in funding sanctioned by the State Board of Education. “LSU’s football team was getting as much money as the Southern system. Even today. Look at the per pupil allocation. It’s unbelievable, Nate says with disbelief.

On October 16, 1972, students from the psychology department, including Sukari, came to the Blackstone Society for help because Professor Charles Waddell, a progressive 27-year-old educator, couldn’t get the resources needed to provide mental health treatments to the surrounding Scotlandville community.

The students drove to Southern Heights to University President Gregory Netterville’s home and shared their concerns and ideas. “We wanted change,” Malik explained. “We got a negative response from Netterville, who said he couldn’t have students running the university.”

It was on then. Students Unit members went from class to class, asking students to join them in seeking positive change.

“We were involved in all sorts of things in the Scotlandville community, engineering and agriculture., Malik confirmed. “We thought faculty could help the community with affordable housing and farming. And we wanted faculty and students to share governance.”

Some professors supported the students privately, and others were “pushed out,” former students thought because they were too progressive. Students United became a massive student movement that spread throughout the Southern University system, including its New Orleans campus. “We wanted Southern to be responsive to and responsible for Black people,” Malik explained.

“Sababu” Harris took on the role of spokesman and peacekeeper for Students United. Whenever the police came on campus, students were instructed to stay indoors to avoid confrontation with law enforcement officers.

Sababu lived with his grandmother in Jennings, Louisiana. He started out majoring in electronics technology but changed to electrical engineering at Southern University’s Baton Rouge campus.

“There were any number of professors that students respected, whose views ran counter to the administration’s regarding our own liberation, advancement, and care, “ Sababu recalls. Engineering Professor Joe Johnson also understood the need to support the students.

“We wanted a more Black-conscious university with ideals that were better for Black students,” he adds. The engineering students joined Students United to form a coalition to address their department’s and others’ needs.

On November 6, 1972, the administration issued an injunction against Students United and arrest warrants for its organizers: Charlene “Sukari” Hardnett, Rickey “Malik Kamibon” Hill, Nathaniel Howard, and Herget “Sababu Taibika” Harris, Malik’s roommate, and Federick “Fred” Prejean. Warrants also named Lewis J. Anthony, Paul Shivers, Donald Mills, and Willie T. Henderson as organizers. However, they weren’t organizers.

On November 9, 1972, at around 12 a.m. Malik and Nat were on the way from a meeting at “Fred” Prejean’s house. Police stopped the car Nate and Malik were in with four other young people. Initially they let them go, but a half mile down the road, “police cars came from every direction,” Malik remembers.

“They put guns to our heads,” Nate recalls. “They asked to see everyone’s ID. When they saw mine and Nate’s, they took us to the East Baton Rouge prison. ‘Talk shit now, you MF,” one officer told Malik. “We had planned a rally for that day. They wanted to arrest us then. Hunt, the vice president of the administration and chief of security, was wearing a trench coat and pajamas. He told us we were expelled.

Malik and Nate believed there were undercover informants among them and that they were under surveillance the whole time. “We were charged with obstruction and interfering with the education process.

The following Tuesday, they went to Sukari’s apartment. The police had warrants for Sababu, Sukari Paul Shivers, a football player, and Fred Prejean. When they learned that Sukari and Fred had been arrested before dawn the morning of November 16, Nate, Malk, Sababu, and several others went to Netterville’s office to demand the release of the arrestees. At least 150 students stood outside.

Netterville told students he was going downtown to the State Department of Education and agreed to rescind the warrants and get the students out. He instructed them to wait for him there.

Twenty minutes after the university president left, all hell broke loose.

“Hunt had called the sheriff already,” and insinuated that Netterville might be in danger or be held hostage by students in his office. That was not true. “Hunt made the third call and asked the sheriff to send officers because Netterville was with many students, but Netterville had already left,” Sababu remembers.

James L. Hunt and Netterville were as grossly responsible for the tragic deaths of Denver Smith and Leonard Brown as the sheriff’s deputy suspected of firing the lethal buckshot and killing them.

“He was not in danger and students were in the outer office,” Sababu adds.

Multiple tear gas canisters flew through the windows. The students hit the floor. “We told the women to stay in the building. Outside, students were running right and left, and the sheriff’s deputies ran behind them. When I came outside the building, I heard them say, ‘There the nigga is. He got a gun.’ I got arrested,” Nate explains.

“We heard pops. They were shooting tear gas canisters at us. A brother fell to my left and another to my right. They were not getting up,” Sababu says about Denver Smith and Leonard Browm. “So, we ran away from the campus.”

Malik believes the Louisiana State Police were aiming at Sababu, who urged students to stay calm during the ordeal because Smith and Brown were on each side of Sababu as they sat on the steps of the administration building. Sababu later turned himself in to avoid being arrested.

The Students United organizers went to court every day for a month. They were banned from Southern University for life and ordered to pay a $2500 fine.

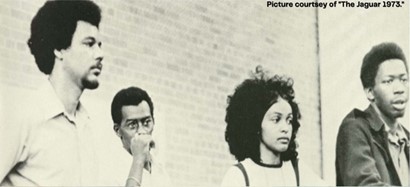

Crime Scene Video *Nate is the tall guy getting arrested in the crime scene video.

NEXT WEEK: THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF A CAMPUS TRAGEDY: STUDENTS UNITED FOOT SOLDIERS TELL ALL

Ola Sims Prejean, widow of Fred Prejean, Brenda Brent Williams, Patrick “Ngwazi” Robinson, and Chester Stevens Speak About Their Experiences. ###

[…] post THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF A CAMPUS TRAGEDY Part 3 first appeared on Black Source […]