Not all babies are born under equal circumstances, and they don’t grow up the same way, either.

By Lindsey Cook, Data Editor

Babies start out with different circumstances. Those differences continue throughout life in America.

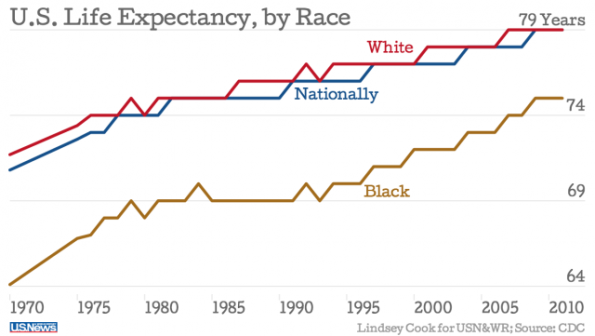

The average African-American male lives five years less than the average white American male.

The death of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, prompted a national conversation about race and the justice system, with many concluding discrepancies exist in policing and sentencing that, apart from race, seem unexplainable.

Health is also far from post-racial. While America has made progress on this front, including through the Affordable Care Act, many gaps persist between blacks and whites.

Issues in health and health care that lead to a shorter life span for black Americans start before birth. The average black baby enters the world under different circumstances than the average white baby, and the gap only grows between birth and death.

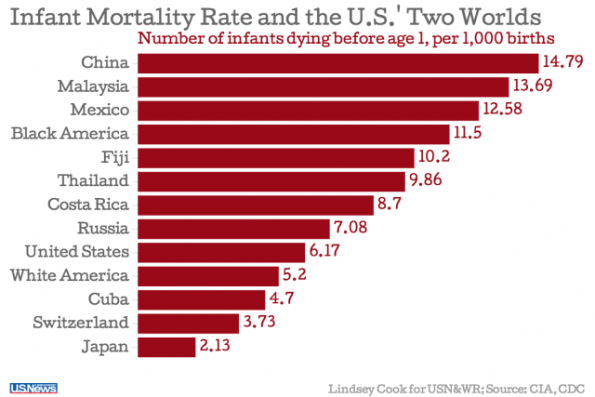

In 2012, about 13 percent of babies born to black mothers had low birth weights (less than 2,500 grams), compared with 7 percent of babies born to white mothers, according to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While the infant mortality rate for white America is 5.2 infants out of 1,000 births dying before age 1, the infant mortality rate for black America is much higher – 11.5 per 1,000 – putting the population subsection nearly on par with Mexico.

It’s difficult to isolate one factor as the cause of lower birth weight and higher infant mortality among black babies – many correlating factors contribute to a perfect storm. Black babies are more likely to be born to younger, less-healthy, less-wealthy and less-educated mothers, who additionally are less likely to be married and less likely to receive prenatal care than white mothers.

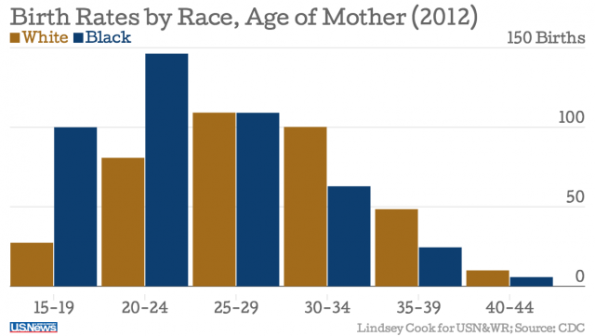

For black mothers, the ages from 20 to 24 are the most common for giving birth, followed by 25 to 29. White mothers give birth later – 25 to 29 is the most popular range, then 30 to 34 – and are far less likely to give birth as a teen.In 2012, one-third of live births to whites were to unmarried women, while more than two-thirds of births to blacks were. Single motherhood means a potential for less stability growing up, but more than that, it means less wealth. The poverty rate for families with married couples was about 6 percent in 2013, compared with 30 percent for families with a female head of the household and no husband present, according to the Census Bureau. Meanwhile, children born to married couples are more likely to finish college, find good jobs and have successful marriages, according to The New York Times.

Also, more pregnancies to black women are unplanned. While 70 percent of births to white mothers between 2006 and 2010 were intended, half of births to black mothers were. This disparity contributes to less preparedness, education and health of the mother. Sexually active black women report less contraception usage than white women.

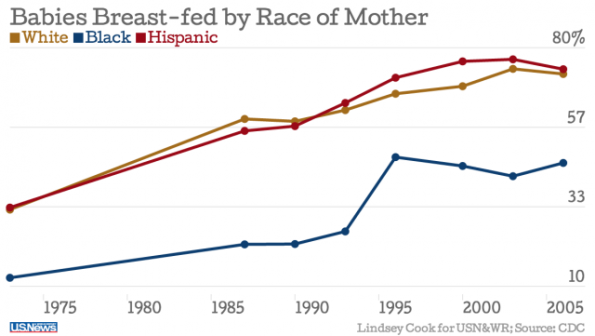

Along the parenting track, breast-feeding has lifelong health benefits for babies, including a reduced risk for hospitalization for lower-respiratory tract diseases in the first year and lower chances for asthma, childhood obesity, Type 2 diabetes and sudden infant death syndrome. For the mother, breast-feeding decreases her risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Despite these and other benefits, black babies are breast-fed at about half the rate as white babies.

Much of that difference can be attributed to less education about the benefits of breast-feeding and fewer options in the workplace for breast-feeding. Prenatal visits present ample opportunities to discuss breast-feeding, but black women are less likely to receive prenatal care. Younger mothers are also less likely to receive prenatal care. Lack of access – meaning a response of, “I couldn’t get an appointment earlier in my pregnancy” – was the most common reason for mothers not getting prenatal care, followed by “I didn’t know I was pregnant” and “I didn’t have enough money or insurance to pay for my visits,” according to a 2003 survey funded by the CDC.

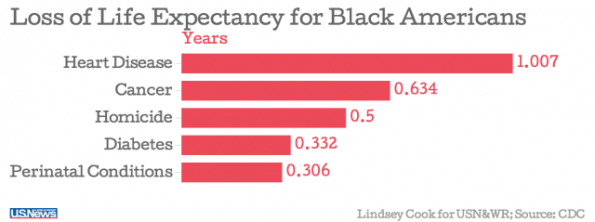

Deaths associated with perinatal conditions – fetal death or the death of a newborn in the first week of life – are responsible for 0.306 lost years of life expectancy for blacks. The list of conditions includes deaths from prematurity and low birth weight, maternal complications of pregnancy, birth defects and birth trauma.

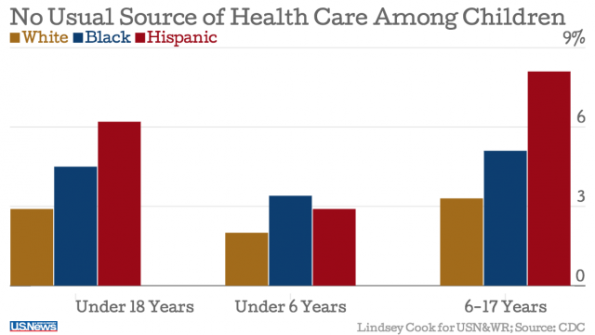

Gaps in health care access can persist for a lifetime. Compared to whites, more black children have no usual source of health care, more black children under 6 have no health visits within a year and more black children visit the emergency room, according to the CDC. Black children also have been less likely to get a full series of vaccinations, with 65 percent of infants between 19 months and 35 months receiving all of their shots in 2012, compared with 69 percent of whites.

Eating habits develop at a young age, but often follow us into adulthood. By high school, there is already a divide between blacks and whites in the consumption of healthy foods, with black students more likely to say they didn’t eat fruits or vegetables, drink milk or eat breakfast in the last week, according to a 2013 survey from the CDC.

Black students also lagged behind whites and Hispanics in physical activity. While 13 percent of whites and 16 percent of Hispanics said they didn’t participate in 60 minutes of physical activity for one of the seven days leading up to the survey, 22 percent of black students said the same. Half of whites were physically active on five or more days, but 41 percent of black students were. More than half of black students watched television for three or more hours a day compared with one-quarter of white students.

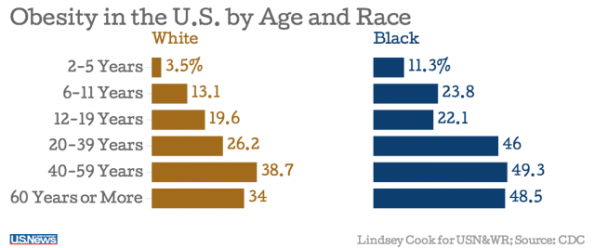

These trends continue into adulthood. While 22 percent of white adults met both the aerobic activity and muscle strengthening guidelines from the CDC in 2012, 17 percent of blacks did. At every age, blacks are more likely to be obese than whites, according to data from the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Part of this is because of factors already discussed – a difference in care dating back to the womb – but economic factors certainly play a role as well. Because blacks are more likely to be in poverty, they may have fewer scheduling options when it comes to work and child care, and may find it harder to afford expensive classes or gyms. For fresh and healthy foods, access is an issue. One report found there were 50 percent fewer chain supermarkets in predominantly black communities than in white communities.

Income and educational differences correlate with obesity in women more than in men. Women are more likely to be obese as education and income decreases. For men, obesity prevalence is similar at all income levels, according to research from the CDC.

Obesity contributes to health conditions that disproportionately affect black Americans and lead to earlier deaths, such as diabetes and heart disease. These conditions require consistent health visits and prescription coverage to manage properly, yet more blacks than whites don’t have a usual source of health care. These long-term conditions are also expensive. More black Americans said they experienced delays or didn’t receive needed medical care or prescriptions due to cost. Factors like these mean blacks are 12 percent less likely than whites to have their blood pressure under control, despite a 40 percent increased likelihood of having high blood pressure.

Cancer-related deaths also account for part of the life-expectancy gap between blacks and whites – accounting for 0.634 years’ worth of lost life expectancy for blacks. In terms of years lost before age 75, black Americans lose nearly 1,796.7 years per 100,000 members of the population due to cancer deaths, while white Americans lose 1,420 years. Although genetics may be somewhat responsible for such differences, socio-economic factors such as diet, lifestyle and a lack of preventive care are far greater contributors. Of the U.S.’ racial and ethnic groups, black Americans have the highest cancer-related death rates and the shortest survival for most cancers, according to the American Cancer Society.

The most common cancers for black men in the U.S. are prostate, lung, and colon and rectal cancer; for women, they are breast, lung and colorectal cancer. The gaps in preventive care have narrowed in the last decade for procedures that lead to early cancer diagnosis, and more Americans overall undergo these procedures and tests. While in 2000, only 20 percent of white Americans and 18 percent of black Americans ages 50 to 75 had colonoscopies, by 2010, 57 percent of white Americans did and 52 percent of black Americans did. Black and white women have mammograms at about the same rate.

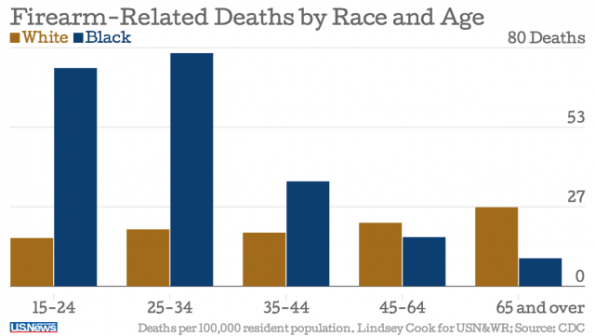

Homicides are responsible for 0.5 years‘ worth of lost life expectancy for blacks. While whites lose 100 years per 100,000 people under age 75 due to homicides, blacks lose more than 800 years. The difference is most stark for males between 15 and 24 years old.

HIV also contributes to differences in years lost: Whites lose 30 years to HIV, while blacks lose 330 years. In 2010, there were 1.8 deaths for white men per 100,000 and 17 deaths for black men per 100,000 because of HIV. For women, rates were 0.4 deaths for whites compared with 8 for blacks. The differences in HIV won’t be going away anytime soon. For women in 2011, 64 percent of all new diagnoses were in African-Americans. For men, 42 percent were in African-Americans.

Differences in HIV education and testing show up early on for blacks and whites. While 87 percent of white high schoolers said they were taught about AIDS or HIV in school, slightly fewer black students said the same – 82 percent. Nearly 20 percent of black students said they had been tested for HIV compared with 11 percent of white students, though the testing disparity makes sense considering differences in sexual activity for students. About 61 percent of black students said they had had sexual intercourse compared with about 44 percent of whites. While 3.3 percent of whites said they had sex before age 13, 14 percent of blacks said the same.

Influenza and pneumonia also show differences: nearly 70 years lost for whites compared with 110 years lost for blacks. Vaccines protect against both of these conditions – the influenza vaccine prevents the flu, which is the most common cause of viral pneumonia in adults, according to the American Lung Association. A pneumococcal vaccine protects against the most common cause of bacterial pneumonia. Again, a difference in preventive care leads to more deaths for blacks and more protection for whites.

Some heartening changes could be on the horizon. The percentage of uninsured Americans dropped from 18 percent in 2013 to 13.4 percent after the rush to meet the April 2014 deadline for the Affordable Care Act’s first enrollment, according to Gallup. The uninsured rate for black Americans has been higher – it was 17 percent in 2013, compared with 12 percent for whites.

But between October 2013 and June 2014, 1.7 million African-Americans (ages 18-64) gained health insurance coverage. The ACA has also made preventive care more affordable and concentrated on several other areas in which black Americans have lagged health-wise, including a projected expansion of maternity coverage to more than 390,000 black women.

But despite recent gains in health insurance, the many racial gaps in health access remain, and will no doubt continue to be a hot topic for policymakers and researchers in 2015.