The 5oth Anniversary of a Student Movement and the Deaths of Denver Smith and Leonard Brown is an Opportunity, Not Just an Occasion

by Angela A. Allen-Bell[1] & Brittany Dunn[2]

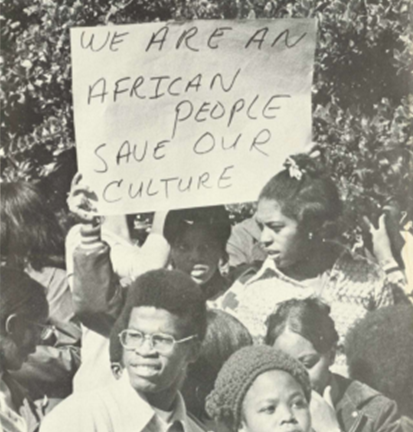

In the 1960s, a movement to challenge segregation took form in the South. And college students at various HBCU’s joined the effort. Louisiana students were no exception. Students at various higher educational institutions around the state were arrested, expelled and/or prohibited from attending classes or returning to campus. This did not silence the effort, however. Various acts of non-violent civil disobedience continued. Louisiana campuses and at the site of segregated establishments from the 1960s to the 1970s saw actions. Louisiana’s crescendo moment came when law enforcement officials descended upon the Baton Rouge campus of Southern University (SU) on November 16, 1972. Within moments, two innocent SU students—Denver Smith (New Roads, La.) and Leonard Brown (Gilbert, La.)—were dead.

The accounts of that morning vary. But, a few circumstances are certain—Smith and Brown were Black, innocent, unjustly killed and their murders remain unsolved. A number of students who participated in the 1972 student movement were veterans. They recently returned from service in the Vietnam War. And they expected rights at home, given their quest for rights on foreign soil. The 1972 student leaders on SU’s campus advocated a noble and legal cause. They wanted to be enriched by the unique possibilities that an HBCU could offer. They wanted agency in their educational experience, which translated into input on matters relative to student life, policy, hiring, retention and curricular. And they wanted the institution to direct resources toward meeting the needs of the neighboring community.

Successful People Despite the Pain

Today, those student leaders are engineers, mathematicians, accountants, IT experts, professors, ministers, authors, government managers, civil servants, lawyers and community activists in their sunset years. They bear the trauma of arrests, misrepresentation, neutralization, termination of their educational opportunities in Louisiana. In order to complete their education they had to separate from their families and go to other states. And still many other injuries that simply can’t be quantified. The murders of Smith and Brown are not the only problem that we are left to grapple with. The 50th anniversary commemoration will fall short of its significance if we fail to approach the day as an opportunity instead of as an occasion. This opportunity is the starting point for: (1) narrative change; (2) truth-telling; and, (3) reparations.

When it comes to narrative change, the student movement of the 1960s-1970s has been explained in terms that serve other interests and not the interests of those who were a part of the movement. Maintaining lies about the student movement makes the need for excessive force believable. It’s time to consider the counter narrative. The student movement must be examined to better understand what the agitation was about. We suspect that study will lead to a collision with the First Amendment and the way the state has continuously chosen to criminalize Black speech and protest. We also suspect it will cast a light on the degree to which violence was used and by whom.

Truth Telling

Truth-telling must be pursued about the following: (1) the intentions White state officials had for SU when they created SU and how that contributed to this tragedy; (2) the vision of Black elected officials who pushed for the creation of a college for Blacks in Louisiana and how that contributed to this tragedy; (3) the way, since the days of chattel slavery, a Black overseer is often placed in Black environments to put a Black face on racism to render it unrecognizable and how that contributed to this tragedy; (4) exactly how much of the events should be attributed to the 1972 student leaders, how much should be attributed to outsiders or other students who were not a part of the student organizing leadership and how that contributed to this tragedy; and, (5) whose lives were impacted as a result of these events.

The 50th Anniversary of a Student Movement

During this truth-telling phase, the above must be analyzed in proper social context. This requires attention to changes in voting practices, the union that segregation forged with Black administrators charged with implementing policy set by all-white boards and the way the FBI operated during this period in history. In the voting arena, a new reality was ushered in for younger Blacks in 1971. That year, the 26th Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified. It gave 18-year-olds the right to vote. Public protests, challenges and activism were of tremendous concern during this era because of the potential influence they could have on this new, impressionable pool of voters. This presented specific concerns for President Richard M. Nixon as he geared for reelection. That concern visited many Louisiana activists during this period. The concern was not minor.

The matter of Black campus organizing became a federal priority. On June 13, 1970, President Richard Nixon established the President’s Commission on Campus unrest. It should not go unnoticed that that Commission, in its final report, concluded that the shootings at Kent State were unjustified. The report said: “Even if the guardsmen faced danger, it was not a danger that called for lethal force. The 61 shots by 28 guardsmen certainly cannot be justified…The Kent State tragedy must mark the last time that, as a matter of course, loaded rifles are issued to guardsmen confronting student demonstrators.” Had that advice been taken in 1970, there would be no 50th anniversary commemoration on November 16, 2022.

Another essential layer of context to consider is the dynamic of Black administrators and all-white boards that segregation created. This outlived segregation and was the reality in Louisiana in 1972. Opportunities for Black administrators were in short supply in the state (because White institutions would not hire them). In 1972, most Black administrators lacked management authority. At the time, some were consensual props. To add another layer of complexity, one must acknowledge the power dynamic that has always existed between a Black subordinate and a white superior in the South. Against this backdrop, we must evaluate the course taken. Time aids our understanding of the other options that existed.

The administration at Fayetteville State University employed internal conflict resolution strategies and decided to honor the requests made by the students. That administration viewed the negotiations as an opportunity to improve its functions. In the end, students felt, they were granted the educational experience they did not mind paying for. When Howard University students demonstrated segregated lunch counters in the state capital, their Black administrators hailed them campus heroes. The University of Vermont, a Predominantly White Institution, embraced its students of color in their demands for increased hiring of faculty of color, increased admittance of students of color and mandatory racial awareness courses.

Context Matters

A final layer of context involves the operations of the FBI during this era. COINTELPRO—short for Counterintelligence Program—started in 1956 to disrupt the activities of the Communist Party of the United States. In the 1960s, it was expanded to include a number of other domestic groups, such as the Socialist Workers Party, the Black Panther Party, those espousing a civil rights agenda and others. J.Edgar Hoover used his power as director of the FBI to neutralize many activists, advocacy groups, dissident voices, artists and innocent citizens. His tactics were often unconstitutional and largely illegal. The Church Committee Report of 1976 established this. The FBI records in this case bear the footprints of COINTELPRO.

According to the FBI report, it was an unidentified caller who reported that President Netterville was being held hostage, but in a separate FBI interview, an administrator reported that President Netterville was removed from the Administration Building at 9:15am. Moreover, in his own FBI interview, President Netterville says that he was not being held hostage when that call was made saying otherwise. The FBI records also show police informants reporting students were armed and openly speaking of assassinating the Governor. Many of the actual student leaders of 1972 have shared their recollections of people posing as students being present in meetings and those people being eager to protest in aggressive ways that were not endorsed by the students nor the student leaders.

Related: Bankrupt Justice

Death nor campus prohibitions nor criminal cases close the curtain on this chapter in history. This shooting, like all murders of unarmed Black men is trauma-producing. These shootings don’t just harm Black people. All people are adversely impacted by violence and unjust treatment. In the case of Black people, this is a part of our inheritance as Americans. We have experienced Black lives taken without accountability since our arrival into the country. When this happens in our community, we experience the same range of emotions that any other community would. We mourn, grieve, hurt and experience rage, despair and profound sadness. But these murders come with an added layer of distress when they visit the Black community because we have to bear the heavy weight of balancing paralyzing sorrows and the lumbering cry for accountability.

That is a unique aspect of loss known too often to the Black community alone. Our souls have to find space in these situations to store the simultaneous wounds produced by systems and structures who witness our plight, but pretend not to notice. We carry intergenerational trauma because of the years that we have lived this existence. Our frames become fragile and our psyches worn with the crippling health effects of years of this type of existence.

The 50th Anniversary of a Student Movement

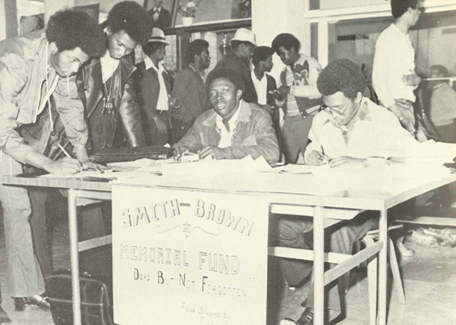

Thirdly, we think reparations are in order. SU has already undertaken some significant steps here. They have named a building, marked the location, done regular programming, archived the history and have openly acknowledged the tragedy. We think these are all important acts of reparation, but this hour demands more. We must embrace a more expansive count of victims beyond Smith and Brown and their families. The student witnesses are victims. The student leaders who were criminalized and/or prevented from returning to campus are victims. The faculty and staff that supported the movement are victims. The children born to parents involved, either directly or indirectly, are victims.

Five days after a similar tragedy at Kent State University, an apology was given and President Nixon said “When dissent turns to violence, it invites tragedy.” In 2020, an apology was extended for the tragedy at the University of Mississippi. In 2021, Mississippi’s governor offered an apology for the tragedy at Jackson State University. Also, in some of these instances posthumous degrees were given. In others, directives that prevented students from returning to campus were dissolved. We call attention to these actions and plea for Louisiana officials to take inspiration from this. We advocate remedies that will help this expansive class of victims heal and for those that will further the reconciliation process.

It is fitting to begin that conversation this year. None of this work has ever been attempted. Instead, we have taken the easier paths of reducing the day to a “hashtag,” a “photo-op” or a “remembrance” then we go through another year and complete the ritual. November 16, 2022 is an opportunity, not just an occasion.

[1] B. K. Agnihotri Endowed Professor of Law at Southern University Law Center (SULC).

[2] Third-year law student at SULC and Prof. Bell’s research assistant.

[…] is the starting point for: (1) narrative change; (2) truth-telling; and, (3) reparations,” wrote Allen-Bell and Dunn in an article exploring how Southern University was one of several high-profile […]