THE BLACK AGENDA GOES BEYOND POLICE REFORM

By C.C. Campbell-Rock

The national debate over whether the anti-racism protests, spawned internationally by the police murder of an unarmed black man, George Floyd, in Minneapolis, constitute a moment or a movement is dominating news cycles, alongside the coronavirus. As the dialogue continues, the question of defunding the police and what real police reform looks like dominates the discussion.

The impact of the protesters’ call for an end to the killing of unarmed black and brown people is taking shape across the nation. Cities like Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York, and others are moving funding from the police and investing in marginalized communities. Congress has put forth a Heroes Act, which includes reducing qualified immunity, a ban on chokeholds, and independent investigations of police shootings.

Whether the calls for police reform is a moment or a movement, a survey of the landscape of America shows that the broader anti-racism movement is continuing simultaneously. Confederate monuments, confederate flags, and statues of those who supported slavery and were overtly racist are coming down, to Donald Trump’s, and other white supremacists’ dismay. Mississippi, which erected its state flag, with the Confederate bars and stars flying at the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865, last week took down the main symbol of the Confederate States of America.

What has been ignored for the past 155 years but now is finally acknowledged by whites is that the white men who created, ran, and posted up for the Confederacy were American traitors, who tried to overthrow the U.S. government to keep black people enslaved and working for free, under the penalty of death. They lost the war but continued to fight for their “Lost Cause” by erecting statues in honor of people who committed treason and caused the deaths of 600,000 Americans.

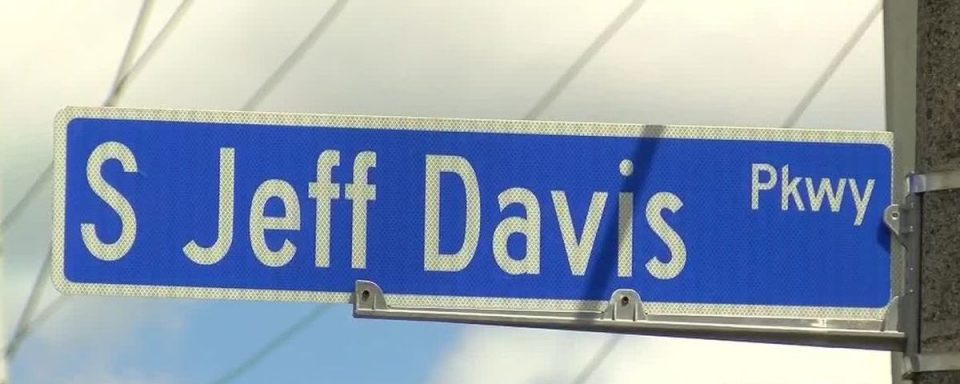

It is worth noting that in New Orleans, the City Council is forming a commission for the renaming of streets, many of which are named for members of the Confederacy. However, there are numerous statues and busts honoring these traitors that still should come down. For example, the statue of Edward Douglass White, Jr., the ninth Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court stands in glory outside of the Louisiana Supreme Court, on which he once sat.

White’s statue should come down because not only did he fight for the Confederacy, he also took up arms in the Battle of Liberty Place and was a self-avowed member of the KKK. White also was on the U.S. Supreme Court and affirmed the so-called “separate but equal” decision in the New Orleans-based case of Plessy v. Ferguson which ushered in a half-decade of legal segregation, American apartheid, across America.

But while these welcomed measures are being taken, civil rights leaders, academicians, and grassroots activists have long called for an end to intentional structural racism that has plagued black and brown communities and marginalized, suppressed and oppressed people of color such that the majority has not been able to achieve the American dream.

Eddie Glaude, Chairman of Princeton’s Center for African American studies and a MSNBC contributor said back in 2018, “We are at an extraordinary crossroads in this country. We’re right back where we’ve always been,” he said citing the days after Reconstruction and the modern Civil Rights Movement. “We have to make a decision, whether or not we’re going to be a racist nation.” In 2019, Glaude explained how embedded white supremacy is in America.

Last month, in the wake of ongoing protests and a reexamination of the work of author James Baldwin, which Glaude has captured in his new book, “Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own,”, Glaude said, “America has met moments of change before but can this generation avoid repeating the mistakes of the past to bring change to racial justice and American culture? And we will have to decide once and for all, if we will be a truly multiracial democracy.”

Meanwhile, thousands of Black activists from across the U.S. will hold a virtual convention in August to produce a new political agenda that seeks to build on the success of the protests that followed George Floyd’s death.

The 2020 Black National Convention will take place August 28 via a live broadcast. It will feature conversations, performances and other events designed to develop a set of demands ahead of the November general election, according to the Associated Press.

The convention is being organized by the Electoral Justice Project of the Movement for Black Lives, a coalition of more than 150 organizations.

“What this convention will do is create a Black liberation agenda…rooted as a set of demands for progress,” said Jessica Byrd, who leads the Electoral Justice Project.

At the end of the convention, participants will ratify a revised platform that will serve as a set of demands for the first 100 days of a new presidential administration. Participants also will have access to model state and local legislation.

“We’re going to set the benchmarks for what we believe progress is and make those known locally and federally,” Byrd said.

I’ve been both energized and outraged, said Marc Morial, NUL President & CEO.

“This is a time for America to wake up, Morial said, citing the international response to the murder of George Floyd. He’s gotten calls from. New Zealand and Australia for interviews on the American response to the anti-racism protests.

“I’m hopeful this is a movement not a moment when people can restructure and rebuild.,” American society,” Morial told Judge LaDoris Cordell a member of the commonwealth club, who moderated a discussion featuring Morial and Michael Tubbs, the mayor of Stockton, California.

“Voting rights, Black political participation, disparate killing and abuse of Black people by police; increasing White supremacy; and disparities in economic and educational systems will remain among the leading issues faced by African-Americans this decade. This according to a compilation of the highest profiled stories and reports between 2010 and 2020,” Hazel Trice Edney wrote in the Charleston Chronicle in January 2020. “Given the weight of these issues and others that have lingered from one decade to another, there is no doubt they will continue to fuel the civil rights agenda for years to come,” she wrote.

But that was before George Floyd’s killing and the ongoing killings and assaults on black and brown bodies that persists in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder.

Since then, the pace and demand for racial justice has accelerated. Demonstrations are planned, like the commemorative March on Washington, which hopes to draw millions to demand racial and economic justice.

Beyond protesting is the arduous task of changing how black people are perceived by racist whites and the near impossible task of securing the debt that is owed to American blacks.

Clearly, central to any change is the dismantling of white supremacy and legislation crafted by racist white elected officials in local, state, and federal governments (voter suppression laws, gerrymandered electoral districts, denial of social programming, prohibiting equal opportunities in contract procurement, equal education, etc.) and those in authority who hold the levers of power and access to corporate budgets (the exclusion of black and brown people at management and decision-making levels).

“Black people alone can’t reform white racism,” said Morial, who was mayor of New Orleans from 1994 to 2002. “It takes white people to do it. Where black people are not is in all-white conversations, when the question of race comes up. Usually, it comes up when someone says something offensive because people think they are in safe company. It’s in that moment that white people have to fight back. That is so critically important.”

Morial’s comment hits on the core of the problem that is blocking black progress. Nonetheless, there is power in numbers and the path to opportunity has always and still does lead to the ballot box. To secure equal rights and protection of their constitutional rights, black and brown people must turn out to vote in droves and elect people who have, beforehand, adopted an agenda that includes these communities’ needs.

Into the discussion of creating a 21st century black agenda has steps Nikole Sheri Hannah-Jones, an American investigative journalist known for her coverage of civil rights in the United States. In April 2015, Jones became a staff writer for The New York Times, where she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in 2020 for her work on the 1619 Project. Also, in early 2015, Jones, along with Ron Nixon, Corey Johnson, and Topher Sanders, created the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting.

Most recently, Jones has become a frequent contributor on news programs. A gutsy, unapologetic black woman, Jones has put the demand for reparations squarely on the table.

Whatever measures are taken up to level the playing field relative to racial justice, it’s a no-brainer that reparations can accomplish this more than any other remedy.

In the past, there has been little to no debate about the need for reparations for both slavery and Jim Crow. However, in the wake of democratic presidential candidates calling for reparations in 2019, including Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, the discussion went mainstream.

However, a recent poll shows that the majority in America is not yet ready to pay up, even though America paid reparations to Japanese-American families whose relatives were placed in internment camps during WWII.

The Reuters/Ipsos poll released Thursday, June 25, 2020 found that 1 in 5 respondents said the U.S. should use “taxpayer money to pay damages to descendants of enslaved people in the United States but “an overwhelming majority still opposes payments meant to address the legacy of slavery and tackle the persistent wealth gap between Black and white Americans.”

“The results were sharply divided along partisan lines, with 80 percent of Republicans saying they’re opposed to reparations while about a third of Democrats said they are supportive. The results were also split among races, with 10 percent of white respondents supporting the idea and half of Black respondents backing it,” according to The Hill.

BET founder Robert Johnson this year called for a $14 trillion dollar slavery reparations payment. “Wealth transfer is what’s needed,” he argued. “Think about this. Since 200-plus-years or so of slavery, labor taken with no compensation, is a wealth transfer. Denial of access to education, which is a primary driver of accumulation of income and wealth, is a wealth transfer,” he told CNBC.

Although reparations remain a dream deferred, blacks are still calling for reparative justice.

To repair or not to repair is to be determined. But one thing is certain, racial injustice must be addressed, if this nation is to return to a peaceful society. The continual denial of justice cannot stand. Surely, the peaceful revolution, which is being televised, and the uprising against racial injustice will not cease until substantive changes are made.

[…] Anti-racism isn’t a purity test, as Cowan claims. I see it as an accurate description of anyone who […]

[…] by CC Campbell-Rock […]