Push On Post-Incarceration

Dion M. Harris

Women persist, despite unequal wages, a widening wealth gap and the daunting challenges of gender bias, abuse, neglect and lax advocacy.

A new exhibit called “per(SISTER): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana” addresses these social ills head on at Newcomb Art Museum, inside Tulane University’s Woldenberg Art Center, on Newcomb Place at Newcomb Circle. The show closes July 6.

Among the states, Louisiana has ranked in the top ten nationally for its high incarceration rates since 1986. From 2005 to 2018, Louisiana ranked first in the nation – and the world – for its incarceration index, according to Loyola law professor Bill Quigley, imprisoning 712 people per 100,000 compared to a national average of 450 people per 100,000. Quigley is a nationally- renowned prison reform advocate and director of the Loyola Law Clinic and the Gillis Long Poverty Law Center.

Women are one of the fastest-growing populations of incarcerated individuals in America. In 1910, according to per(SISTER), women were 5.5 percent of the U.S. inmate population. Over the past 40 years, however, the number of women entering lock ups has increased 834 percent. More than 1 million women now find themselves under correctional supervision (probation or parole).

In November, a Prison Policy Initiative report determined that 219,000 women are incarcerated in the United States. Most of these women are being held in state prisons (99,000) and local jails (89,000). The exhibit points out that 82 percent of them are being held for nonviolent offenses.

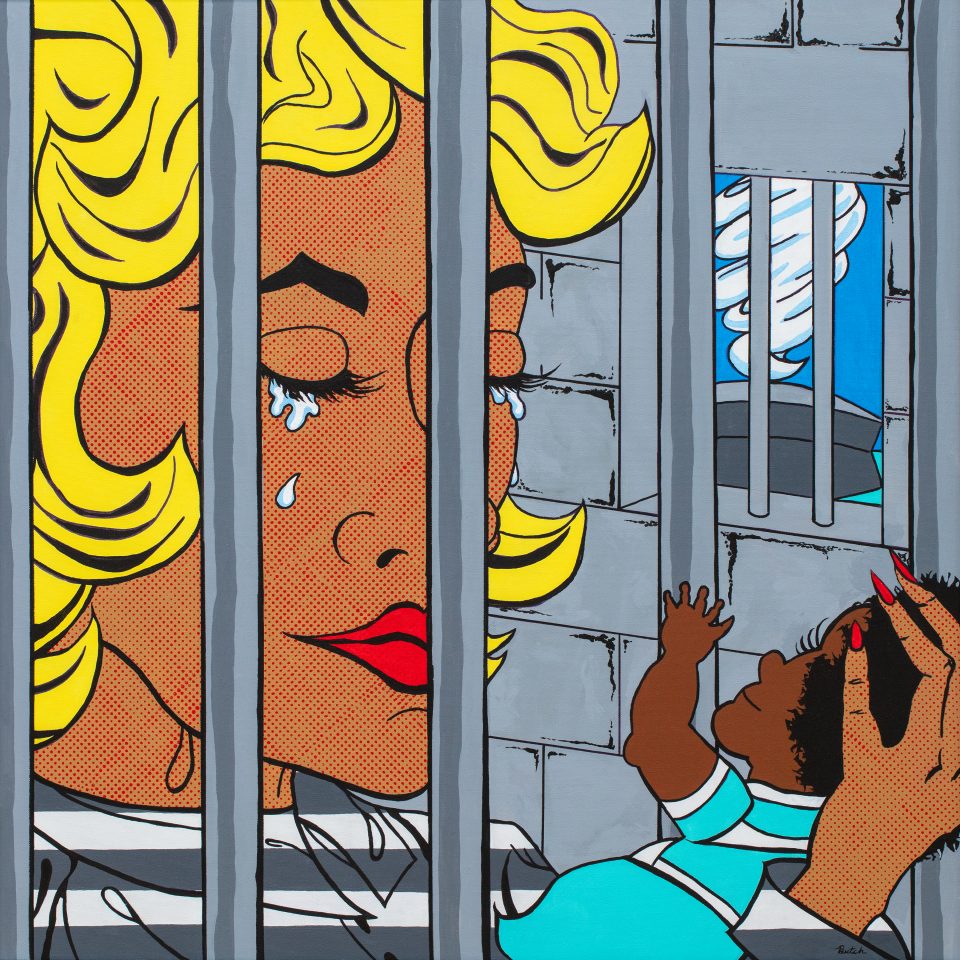

“The percentage of mothers who are incarcerated [is the most incredulous fact I’ve learned in working with per(Sister)]. Eighty percent are mothers,” said Miriam Taylor, external affairs manager for Newcomb Art Museum. “Seventy nine percent of them are mothers of small children. A majority are mothers or grandmothers. It’s devastating. It’s something people are not really aware of. When you remove a caretaker, that’s a family.”

In four airy galleries under Tulane’s shady oaks, more than 30 of the former incarcerated and currently-incarcerated have their say. The women tell their stories in their own words and with their own voices, sharing oftentimes intimate details of their lives.

“Every one was so totally open and willing to tell their stories,” said Allison Beonde, whose portraits of the persisters anchor the exhibit. “You do not always get that in the world.”

The women are presented in black-and-white portraiture, in groups of six. Excerpts from their transcribed interviews accompany the photos. Listening stations allow visitors to tune in to short sound recordings of the persisters as they candidly recount what went wrong for them in their lives.

“We wanted to make sure the women were honored and represented the way that they would want to be,” Taylor said. “We were really intentional with self-representation. The women are experts in their experiences. Anyone can relate to them.”

“Per(SISTER): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana” is the result of three years of meetings, conversations and work among Tulane faculty, students, artists and community activists.

“It was important for us to be authentic. We had to figure out how to do it, how to set the right tone and how to send our message [of demanding social justice],” Taylor said.

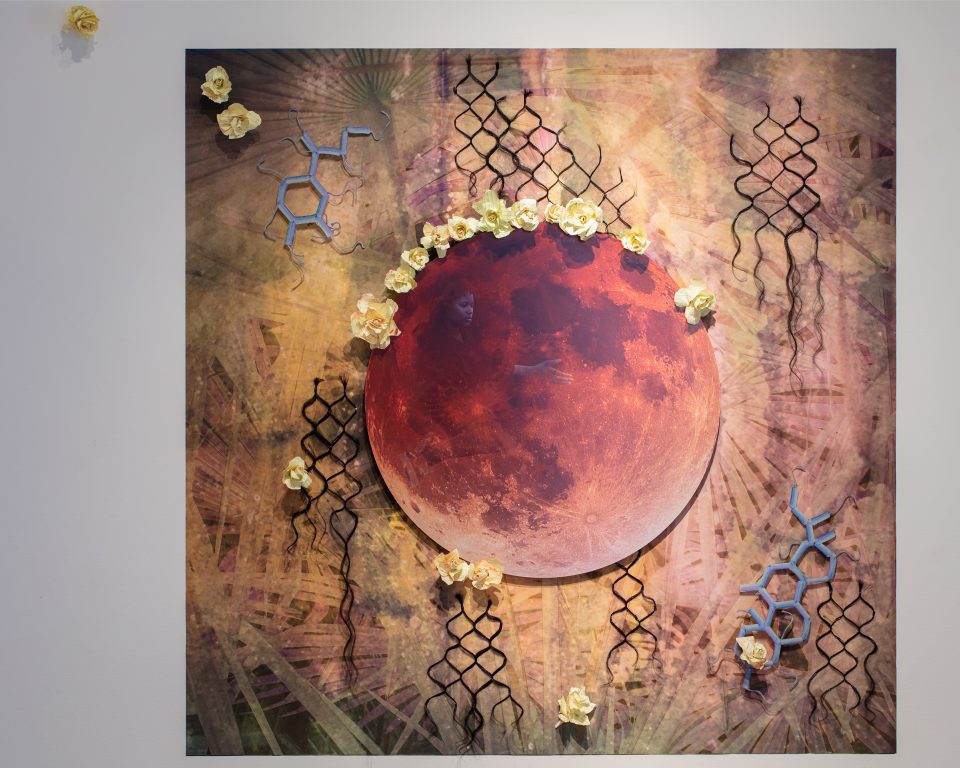

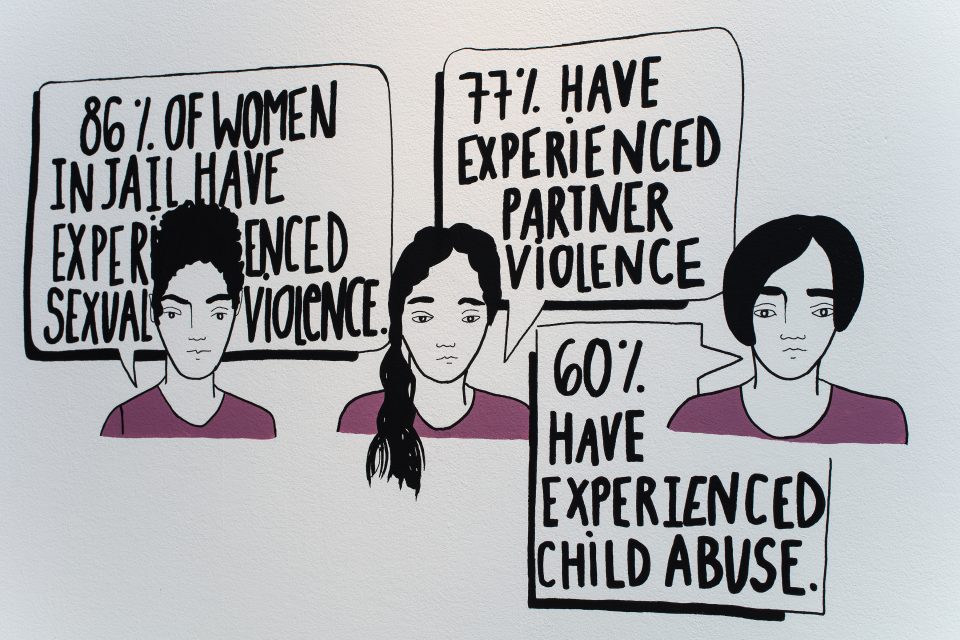

Beonde’s portraits are joined by other artists’ works that are inspired by the per(SISTERS)’ stories. Included are several illustrations by Taslim van Hattum, which explore the statistics; oil and acrylic paintings on canvas; other photos; a beaded “Life Quilt,” depicting the names of 107 women serving life sentences in 2017 Louisiana; sculptures; multimedia works; installations and even a ceremonial robe. Songs inspired by the per(SISTERS) provide an exhibition playlist.

A timeline of socio-historical legal facts and firsts snakes along the wood plank floor through all four galleries. Among those highlights:

- 1829- Eastern State Penitentiary at Philadelphia was the first modern U.S. prison. Here, the instrument of solitary confinement was introduced to America.

- 1844- Louisiana leases state penitentiary and the labor of the incarcerated to McHatton, Pratt & Co. The state would continue leasing incarcerated people to private companies until 1900.

- 1848- Louisiana passes a law making all children the legal property of the state if they are born to an enslaved African-American woman incarcerated for life. Eleven of these children were sold at auction for $226 to $1,010 per child.

- 1870- Louisiana judges impose “perpetual imprisonment” for fourth offenses and longer sentences on people with prior convictions.

- 1995- Mike Davis, urban theorist, coins the term “prison-industrial complex” to define the national trend of expanding imprisonment and prisons, regardless of need.

- 2016- The United States has 102 federal prisons; 1,719 state prisons; 942 juvenile correctional facilities; 3,283 local jails; and 79 Indian Country jails.

Andrea Armstrong, a Loyola University law professor, provided the timeline.

“It’s backed up by statistics. It shows how intensive an issue this is,” Taylor said. “It helps to bring a human face to the statistic.”

‘Just what is criminal?’ is what per(SISTER) implores visitors to consider. Is it the domestic violence reporters who get swept away in “dual arrests” for reporting the crime against them? Or is it the sex workers, fulfilling a market demand by men for sexual services? How about the various other misdemeanors many women find themselves serving time for?

Among inmates in 2014, women earned an average salary of $13,890 annually compared to $19,650 for men, according to per(SISTER). Two-thirds of these women endured a chronic medical condition compared to an estimated 50 percent for men.

Seventy seven percent of incarcerated women are surviving previous partner trauma, 86 percent of them have suffered sexual violence and 60 percent of them were physically abused by caregivers as children.

“I didn’t realize how bad things are for women, compared to men, in Louisiana,” Beonde, a master of fine arts candidate from Florida, said. “How disparate the resources are. Anyone who hasn’t lived through it – you don’t think about, you don’t hear about it on the news, you don’t think about it on a daily basis.”

Since its opening reception on Jan. 19, more than 2,000 visitors had experienced the often-wrenching, but very feminine show by the end of February. A record 800 guests attended the opening, Taylor said.

Monthly programming includes one major panel where experts on the subject matter are brought in to the museum for discourse. On March 22, musicians Lynn Drury, Queen Koldmadina, Margie Perez, Keith Porteous and Sarah Quintana perform new pieces crafted specifically for the exhibition in Freeman Auditorium, at 6 p.m. The next day, Tulane dance professor Ausettua AmorAmenkum’s students present an interactive and interpretive performance in the museum at noon.

“Please come see the art, but we want to provide access for the common good. We want you to be informed,” Taylor said. “I’m so fortunate to be on a campus that encourages us to think outside the box.”

Grim statistics and a plethora of black female faces discussing their descent and ultimate incarceration can take a toll. A curtained-off Sensorial Room greets guests in the third gallery to provide needed relief from the subject matter. The Sensorial Room is outfitted with four club chairs, set in a square. Various soft objects are provided to rejuvenate the senses.

Systemic oppression is an issue close to Beonde’s heart, so she jumped at the chance last April to provide portraits for per(SISTER).

“I think all of them are incredibly strong, incredibly beautiful and incredibly gracious. One of my subjects expressed it best: ‘I am more than my crime.’

“People want to be able to categorize and put a label on people, and it’s often really unjustly by other people,” Beonde said. “Every single woman just blew me away with how strong, beautiful and gracious they are.”

“per(SISTER): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana” is presented by Newcomb Art Museum, 6823 St. Charles Ave. Admission is free and open to the public, Tuesday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturday, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. and by appointment.

I can’t wait to see & hear the collective experiences of these African American women who was incarcerated in these HELL HOLES called prisons!! I’m sure from reading some of the comments in this article I must see & experience these powerfully positive Black women expounding in their own words depicting they experiences! I’m looking forward to checking out this exhibition at Tulane ( newcomb)! Sekou Fela