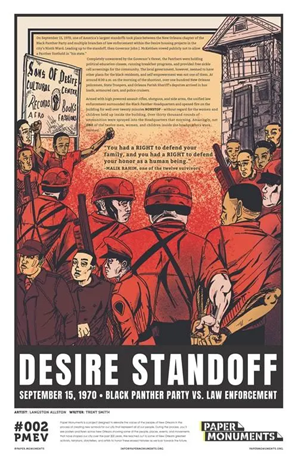

Revolutionary History: Lost and Found, and Lost Again How the Desire Street “Panther mural,” painted in 1970 to chronicle Black history for residents of the Desire housing development, met its end.

by Orissa Arend

In July, art writer Nikki Cormaci emailed me, out of the blue. She was looking for the Bruce Brice mural on Desire Street.

She couldn’t find it.

Later, driven by curiosity, my husband and I drove down to Desire. We discovered the tragic reason why her search was unsuccessful.

But that night, when I got Nikki’s message, I asked her to stop over. We looked at the photos I had taken six years back. Back then, I stood outside the abandoned shopping mall where the mural spanned nearly an entire block.

My last trip out there was on a partially sunny Tuesday morning in February 2017. Four cultural experts from the Louisiana State Museum walked with me. We waded with me through weeds and detritus to pull vines and cut trees away from the back wall of an old shopping mall. The Desire Community Housing Corporation owns the old mall. It stood on an otherwise vacant block on the eastern edge of the Upper Ninth Ward. It is a desolate space forgotten by all the world, except for the occasional squatter and a cluster of graffiti artists.

Revolutionary History

Greg Lambousy is Director of the New Orleans Jazz Museum. Amid the debris, he spotted a long iron rod with a curve like a shepherd’s crook. He used it to pull down a gutter. We were trying to get a better look at what we had come to call the “Panther mural.” It is painted on cinder block, covered over with stucco years ago and relegated to oblivion. It embodies themes of African-American empowerment and militancy from the era of black nationalism.

Not many New Orleanians still remember how powerful the New Orleans Black Panthers were in 1970. Back then some Panther Party members began living in an apartment in the Desire public housing development. The Panthers vowed to stay there to improve conditions. They demanded basic services like garbage pickup – and wanted to protect residents from the New Orleans Police Department. The NOPD patrolled the Desire with a heavy hand, arresting, beating, harassing and even shooting people.

The Panthers had powerful detractors within the NOPD and in Washington, D.C., where FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was determined to eradicate them.

But in the Desire, the Panthers were largely viewed as a source of inspiration and a force for good. Their members acted as champions of the poor, unifiers and revolutionary educators.

After our strenuous, resourceful, and somewhat dangerous clearing efforts, photographer Mark Sindler got a pretty clear angle on the mural where the stucco had fallen away. Propitiously, just then the sun came out.

If you follow the wildly improbable twists and turns of this story, you could conclude that we, all of us, are being led to pay attention. We wanted to notice something that has revolutionary and artistic relevance to New Orleans history.

The recent chapter in this long saga began in the spring of 2016 with a young doctor named Joe Fraiman. Fraiman, chief medical resident at the LSU Medical Center, was driving home from a search-and-rescue training session. But a detour took him by the abandoned, grafitti-splashed mall. He had run into multiple roadblocks because of an acid spill that was being cleaned up. He was on Piety Street, trying to figure out how to get home, when he noticed the building. “It had a presence to it. I had my rescue boots on. And I enjoy these kind of impressive spaces,” Joe told me. So he stopped to take a look. On closer inspection, what caught his eye was a well-preserved art work slowly revealing itself as the stucco fell away from one exterior wall. “There’s something very special here,” he texted fellow medical resident Jenn Hissett who is also an archaeologist.

Revolutionary History

She looked at the pictures and decided that this had a 1970’s Black Panther tone. He didn’t dare tear away more plaster to see what else was there for fear of exposing the art to the weather or attracting vandals. Instead he emailed The Lens and Jed Horne. Horne was the opinion editor of the Lens at the time. Horne put him in touch with me because he knew of my interest in the Black Panthers and the Desire Housing Project.

When I went out to see the mural, I felt like Indiana Jones as Joe walked me down the road along the expanse of weeds and detritus. When he made the discovery, Joe didn’t know he was near the site of the Panther shootout and the day-long Desire standoff of 1970. That is the topic of my book Showdown in Desire, The Black Panthers Take a Stand in New Orleans. and he’s too young to have personal memories of the Panther era. Nevertheless, when the mural caught his eye — especially those afro hairdos and the bandoliers — Joe immediately picked up on the Panther vibe. Preserved on concrete blocks thanks to some miraculous quality of the plaster undercoating, the mural struck him as rare and hidden and precious. Perhaps it had an important story to tell.

As I wandered, this is what I saw: “Amidst Chaos Lies Beauty” read the graffiti on the wall. Chaos aplenty: the dregs of a ruined utilitarian space, wood, busted-up furniture, plaster, nests of vermin. Beauty: yes, flowers, the colorful graffiti, someone’s neat and spacious improv home. And then a startling revelation that I walked right past, easy to miss: what appears to be history.

Peeking out from a wall where plaster was beginning to peel away was a mural painted on cinder blocks. Left to right, it featured what appeared to be one of Columbus’ ships, a slave captain being slain by Black warriors, an African tree and hut, the old Desire apartments and black men with bandoliers protecting them. The graffiti artists had respectfully left this historical memo – the little that is exposed – unscathed.

Revolutionary History

In 2016, I wrote for the Lens, “This is pure conjecture on my part, but the mural could be a history wall. Reading left to right, it tells a story that includes the European “discovery” of America, a slave revolt (that captain being slain by Black warriors) right on up to the Panthers protecting the Desire apartments. Could someone who knows more about art and preservation than I do please come forward and restore this auspicious, accidental find?”

Within weeks, Ricardo Coleman, an adjunct professor at Delgado Community College, contacted me because of the Lens article. He said that he had not seen the mural since he was a child. He had assumed that it, along with Bynum’s Pharmacy which was the building on which it was painted, were both long gone. “So, imagine my surprise when I read your story and learned that it still exists. I can certainly remember that it contained violent and powerful images that stirred up many emotions when I first saw it. Initially, I was afraid of it. I just didn’t understand what it all meant. I can tell you that it definitely seemed to tell a story. But, it also caused me to ask questions about it, and I think maybe that was the beginning of my love affair with history.”

“ One of my teachers told me that it was erected shortly after the Black Panthers’ confrontation with the NOPD,” he went on to say. “It was intended to educate young people just like me about the history of black people in America. I can also remember that while everything in the neighborhood was ‘fair game’ for graffiti, no one ever tagged the mural even back then. …” Coleman’s recollection supported Joe’s and my assumption that the mural dated to the Panther era, but who had created it? Who was the artist?

Revolutionary History

A few months later, I was at a Panther reunion panel organized by Malik Rahim, a Panther back in the day who had gone on to a heroic role in the Hurricane Katrina recovery effort as founder and head of the community group, Common Ground. After the discussion, I approached a man named Wesley Philips who had made comments from the audience that suggested he might know more about the mural. He said he had lived in Desire from 1956 until 1981 and that he remembered the mural well. He confirmed Coleman’s hunch that the artist was probably Bruce Brice, a distinguished New Orleans painter among whose accomplishments was the design of the very first Jazz Fest poster in 1970.

Bruce died in 2014 at the age of 72. But his website was still up and running and so I gave it a look. There, right at the top, stood a decades-old photograph of the mural as it looked when newly painted. You can imagine my surprise and delight. It was the eureka moment. Any need for guess-work about the mural’s origins had been eliminated. But I was still curious to learn more.

The web page shed light on Brice’s purposes as an artist and his fascination with the visual textures, communities and architecture of New Orleans: “I am an artist educating the masses. My goal is to teach . . . to enlighten others about the rich African American experiences, culture, and traditions in this region,” he wrote. “Through various mediums, I am able to link the past to the present and form positive visions of the future.”

From photographs and conversations, we now know that 53 years ago, Bruce Brice was the center of attention as he stood on a scaffold next to this old cinder-block building and painted a mural that spanned the entire back of this building.

The mural’s rich colors captured the vibrancy Brice saw all around him, as Black Panther Party members fed and worked with the Desire public-housing community, then the largest public-housing development in the nation.

Yet here was the mural, relegated to oblivion, much like the history it represented.

Eben Brice, a local businessman in his 30s, was especially pleased by the discovery of his father’s work, slowly coming to life behind the crumbling stucco. Here was proof of something he had only heard about: his father’s social activism as he made the transition to full-time artist in the decade before his son’s birth. The mural, Eben said, was a “living legacy”, evidence of his father’s impact on the city, socially as well as artistically.

Just as I was mulling over how in the world this historical treasure could be documented, appreciated and preserved, Tulane professor and historian Lawrence Powell called me on another matter. Powell has great ideas about how to get just about anything done, so I asked him for advice on preserving the mural. He said he would get right on it and, in his capacity as chairman of the board of the Louisiana State Museum, he did. That’s how I ended up in a pile of rubble with a gaggle of museum experts wielding crudely improvised clearing tools.

Revolutionary History

In another article for the Lens, I wrote: “That’s the latest in a series of improbable occurrences. No doubt there will be others as this piece circulates and the ghosts of our revolutionary past crawl out of cracked stucco and rubbish and years of neglect and clamor to be seen and heard. Now the challenge is to find a home for this relic from the city’s historical past, so long protected by our obliviousness to it.”

Persistent as these revolutionary ghosts had been, when Richard and I went in search of the remains of the mural, the ruined building was gone, the mural was gone – nothing, nada, weeds.

Katy Reckdahl, associate editor at the Lens unearthed this last bit of information: After Hurricane Betsy, the city had donated the steel-framed shopping-center building to the Desire Community Housing Corporation, said Wilbert Thomas, Sr., 74, who has been president of the nonprofit for the past 30 years.

They added a washateria there for people who lived in the Desire, made sure there were pharmacists and other services. And they arranged for Brice to paint the mural.

Thomas vividly remembers the artwork, because his best friend, Johnny Jackson – a member of the Panther Party and a future state representative and City Councilman — ran the Desire Community Center, where Panthers served breakfast and tutored and worked with children.

“When we were mentoring the young girls and guys, we would look at the mural and talk about it,” Thomas recalled. “If people toured the building, we would talk about the mural.”

The structure was 50,000 square feet and the mural spanned the whole back of the building, from Industry to Florida Avenue.

Before the demolition, The Desire Community Housing Corporation had made plans to renovate the building and re-open it. As they planned, they had discussed ways that they could revive the historic mural, he said.

Then, a few years ago, in December 2019, Thomas got a call. A demolition crew was on the site. Backhoes and bulldozers were tearing into the building.

Thomas ran to his car and sped to the building, a few minutes away. He stood in front of the bulldozer, said that he hadn’t given anyone permission to tear down the building. The work crews called their office and realized their mistake. Their order was for a nearby structure. They had demolished the wrong building, they said.

Revolutionary History

Turns out, the crews were supposed to demolish a building next door. But that building had already been demolished. So they dug into the Desire’s building. By the time Thomas arrived, the building was in pieces. Nothing could be saved.

“It was a mistake, as they say,” said Thomas, who is trying to figure out how to rebuild it. But also, he mourns the structure itself. “All the historic stuff we had,” he said.

The demolition brought out conspiracy theories in a few people who live nearby, who tell Thomas it doesn’t sit well with them. “All the buildings you could have torn down. Why choose this one?”

He wonders too, even as the Desire Community Housing Corp. makes plans to rebuild. He’s determined to have another building there. “And we gonna get us another mural,” he said. “I promise we’ll get another one.”

For me, the revolutionary ghosts had been persistent.

But in July, when Richard and I went in search of the mural, I saw first-hand that the ruined building was gone, along with the mural itself.

Now, thanks to Wilbert Thomas, I know what happened.

If we hadn’t documented what we’d seen, I would have seriously asked myself if this memory had been a dream.

But since I do have the photographs and the stories, I feel obligated to share with the world, to educate others like the mural educated me.

Orissa Arend is a mediator, psychotherapist, and writer. You can reach her at orissaarend@gmail.com. This piece includes reporting by Lens deputy editor Katy Reckdahl.

Chaos Beauty

Desire Housing Front

Desire Mural

Joe Fraiman

Panther Houses & Tree

Zeak