New variants will pose a challenge, but early signs suggest the shots will still boost antibody responses.

By Cassandra Willyard

This article first appeared in The Checkup, MIT Technology Review’s weekly biotech newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Thursday, and read articles like this first, sign up here.

Last week I came down with some kind of bug. So I got to play one of my least favorite games: “Covid or Not Covid?” In my case, two rapid tests were negative, so probably not covid. But many other people have been testing positive. Covid hospitalizations in the US rose nearly 16% during the third week of August. Even Jill Biden got covid this week. Data suggest we’re at the beginning of a fall wave. And with students returning to schools and workers returning to offices, I’m sure I’m not the only one who is thinking about covid vaccines. It’s been a year since a booster was released. And while the latest wave isn’t likely to be as bad as the tsunami we experienced in 2021-2022, there’s a lot of uncertainty about what the next few months look like.

So for this week’s Checkup, let’s take stock of where we’re at. Where are the updated shots? And how do they stack up against the new variants?

When will I be able to get my next covid shot?

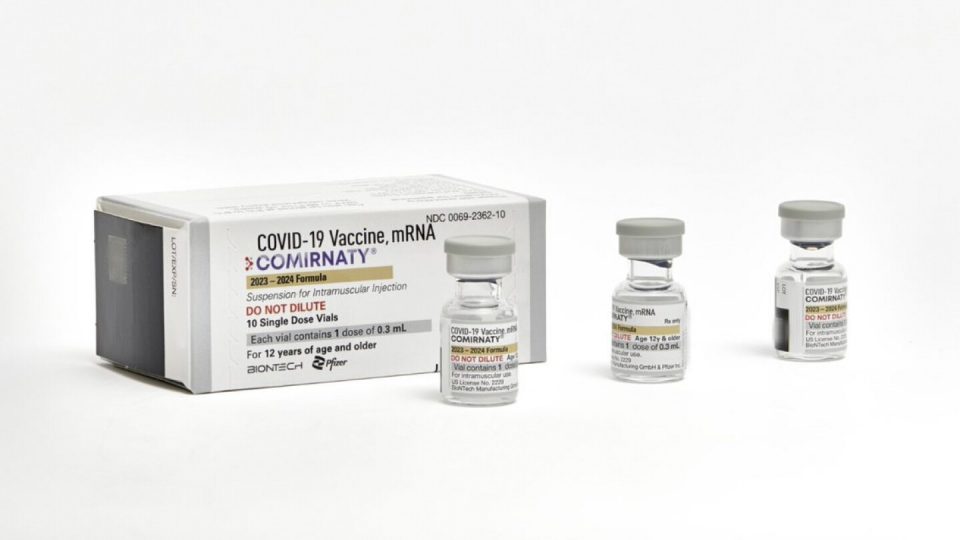

Depending on where you live, as soon as this month. At the beginning of the summer, the US Food and Drug Administration decided that the vaccine needed a refresh. The agency advised manufacturers to develop vaccines targeting XBB.1.5, a descendent of omicron and one of the dominant variants circulating at the time. Pfizer, Moderna, and Novavax have done that. Now they’re waiting on FDA approval, and guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on how the shots should be administered. That should all happen by mid-September. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the body that provides guidance on who should get vaccinated and when, is set to meet next week, on September 12.

In Europe, Pfizer’s new vaccine is already approved. The European Commission greenlighted the shot last week. And this week regulators in the United Kingdom followed suit. The first shots should be going into arms soon. Those at greatest risk of developing serious illness in the UK will be eligible for the new shot starting September 11.

But XBB 1.5 isn’t the only variant circulating these days. How worried should I be about newer ones?

XBB variants are still causing the majority of infections in the US. But a couple of other variants have been gaining ground. According to CDC estimates, EG.5 is now responsible for about 20% of covid-19 cases in the US. That’s more than any other single circulating variant. A variant called FL 1.5.1 comes in second, making up 15% of cases. These viruses don’t seem to cause more severe disease, but they are more adept at evading the body’s immune response.

Related: Signs You May Have Had COVID 19

Scientists are also paying close attention to a variant first detected in early August known as BA.2.86 or, by its nickname, pirola. This variant is notable because it’s so unlike any of the other versions circulating. “What really caught people’s attention is that it had over 30 mutations in spike, so a very substantial genetic change,” says Dan Barouch, an immunologist at Harvard University, referring to the sharply protruding protein the virus uses to gain entry into cells. It’s only the second time that SARS-CoV2 has made such a big leap. (The first time was the jump from delta to omicron, a shift that led to the deadliest covid wave to date.) The worry is that this massive change in sequence might make the virus harder for our immune systems to recognize and fight off.

But preliminary data trickling in suggests that fears about pirola may be overblown. In a preprint posted on Tuesday, Barouch and his colleagues looked at blood samples from 66 individuals, some who received the bivalent booster in the fall and some who didn’t. The group also contained a subset of people who had been infected with XBB.1.5 in the past six months. Neutralizing antibody levels against BA.2.86 were comparable or higher than levels against XBB.1.5, EG.5, and FL.1.5.1. So this variant doesn’t seem to be much more immune evasive than other variants. “That was a bit unexpected, and good news,” Barouch says.

Those results are roughly consistent with what labs in China and Sweden reported in recent days.

About this autumn’s covid vaccines

BA.2.86 has been “downgraded from a hurricane to not even a tropical storm,” Eric Topol told USA Today, adding, “We’re lucky. This one could have been really bad.” But the data thus far is preliminary. And even if BA.2.86 is just a light rain shower, that doesn’t mean it won’t lead to problems in the future. “It’s BA.2.86 (Pirola) descendants that worry me more than the current variant per se,” wrote T. Ryan Gregory, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Guelph, on Twitter. “The concern will be that it will continue to evolve and its descendants will have traits that make it successful at reaching new hosts.” In fact, BA.2.86 already has developed a sublineage.

So if BA 2.86 isn’t causing the surge, what is?

Probably a combination of factors, including waning immunity. The last vaccine update, the bivalent shot, came out a year ago. “It’s been quite a long time since boosters were provided for covid, and those boosters did have a relatively low uptake rate in the population,” noted Johns Hopkins virologist Andrew Pekosz in a recent Q&A. Plus, the new dominant variants are more adept at evading our immune system than previous viruses.

How well will the new vaccines work?

That remains to be seen. Both Moderna and Pfizer have reported that the new shots elicit a strong antibody response against the XBB variants, as well as EG.5.1, FL 1.5.1, and BA.2.86.

Borouch and his team also found that XBB.1.5 infection appeared to boost neutralizing antibodies against BA.2.86, a hopeful sign that the vaccine might also help fend off the new variant.

But protection will likely fade quickly, just as it did with previous covid vaccines. “We know that the durability of the mRNA boosters is relatively limited,” Barouch says—on the order of six months.

An updated shot will be most important for people who are immunocompromised or vulnerable in other ways that leave them at high risk for developing severe disease. Whether the shot will be useful for younger, healthier people “is a source of some controversy amongst experts in the field,” Barouch says.

We know the vaccine won’t protect against any and all covid infections. But it could lessen the severity of the illness. “I still might get [covid], but it just might not be as uncomfortable,” says John Wherry, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania. An updated shot might also reduce the risk of developing long covid. “There’s still some chance of getting long Covid every single time you get infected,” Wherry says. But if a robust immune response can keep the virus from spreading beyond the upper respiratory tract, “I think the chances of long covid are probably a little bit lower.”

That’s a win in Wherry’s book: “I’ll take it.”