Enslaved Black people dreaded New Year’s in Civil War-era America, when they might be separated from loved ones. Just don’t tell the people yelling about “critical race theory.”

On this New Year’s Day, it’s a good bet thatRhode Island state Rep. Patricia Morgan and the one Black person she knows will not be sitting down to eat black-eyed peas and collard greens together.

It’s an even safer bet that she and her fellow Republicans will spend zero mental energy on the history of the New Year as a terrifying time for enslaved people in America.

Rep. Morgan, you may recall, tweeted a few days ago that she “had a black friend”—emphasis on the past tense—but this unnamed Black token had recently become “hostile and unpleasant,” which the Rhode Island lawmaker concluded must be because of critical race theory, because she herself hadn’t done “anything to her, except be white.”

CRT, according to Morgan, is the issue that’s really “divid[ing] us because of skin color.”

This is really quite the take during an era in which Confederate flag-waving insurrectionists have stormed the U.S. Capitol building, the FBI identified white terrorists as the greatest threat to national security, members of Congress openly aligned with self-identified white nationalists and promoted their ideologies, hate crimes against Black folks rose precipitously, and Rep. Morgan herself proposed one anti-CRT bill and stonewalled another that would incorporate the teaching of Black history in Rhode Island schools.

It’s tempting to think that Morgan is just misinformed about CRT—an esoteric legal concept for examining systemic racism that no Rhode Island school is teaching, and that the far right has become obsessed with over the last year. But in a later appearance, Morgan unwittingly admitted that her issue isn’t with CRT, but with the idea that history might be taught in a way that fully acknowledges how anti-Black racism has defined every aspect of America, taking full stock of the devastation caused by white American supremacy. That would be too much of a bummer, according to Morgan, who claims that “with CRT, there’s no redemption,” because it does not focus on the “good part of our history.”

That’s really just a way of saying that she opposes a history that isn’t filled with supremacist fables and other ahistorical nonsense. Not to mention that she also isn’t a fan of white folks—after centuries of omitting Black folks from the historical record—having to share the historical spotlight.

“I’m genuinely concerned that critical race theory—this centering of the Black experience, this making race the center of everything in our society—is really dangerous,” Morgan said in an interview. “And it’s chipping away at the things that bind us together as Americans.”

This is what CRT opponents truly fear, summed up by Morgan. Perhaps because she would prefer that Rhode Island schoolkids not know that their home state’s “General Court of Election”—meaning Morgan’s own legislative predecessors—passed a law in 1652 that ended lifelong Black enslavement in two cities, and would pass another law proscribing Native slavery in 1676, only to completely ignore that legislation in favor of racial capitalism.

Laws curtailing slavery would also be passed in the state in 1774, 1784, and 1787, though those didn’t end the barbaric system either. In fact, “almost half of all of Rhode Island’s slave voyages occurred after trading was outlawed,” as USA Today reported. When the American Revolution began in 1775, “Rhode Island was the largest slave trading colony in British America,” according to Leonardo Marques, author of The United States and the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Americas. Newport, and then Bristol, were major ports in the trans-Atlantic importation of human beings trafficked from Africa to the colonies in the 18th century, and had more enslaved Black folks per capita than any New England state of the colonial era.

The state would finally constitutionally abolish slavery in 1843.

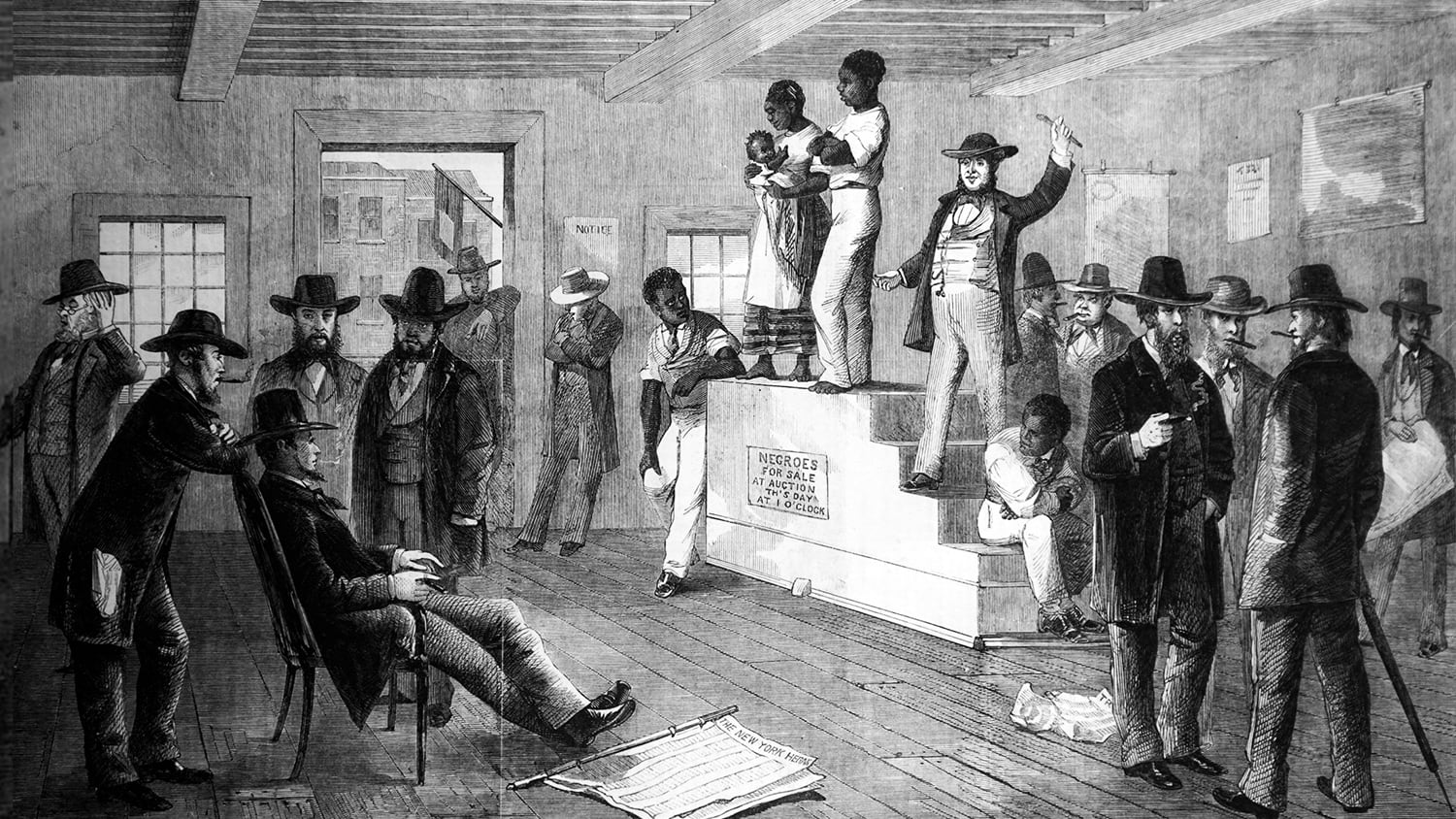

While it’s now considered a celebratory moment across the U.S., the end of the year was filled with trauma and trepidation for Black folks living under the yoke of slavery. Enslavers would settle their accounts as the year came to a close, and that meant those they enslaved might be hired out to other enslavers, or sold on the first day of the year. Among enslaved Black folks, New Year’s Eve was spent worrying that they might be ripped from family and loved ones, auctioned off to the highest bidder to erase an enslaver’s debt.

And as such, New Year’s Day was known as “Hiring Day” or—in words that more precisely named the cruelty they experienced—“Heartbreak Day.”

“Of all the days in the year, the slaves dread New Year’s Day the worst of any,” Lewis Clarke, who fled enslavement and became an outspoken abolitionist, stated in 1842, one year before Rhode Island banned legalized racial bondage. “For folks come for their debts then; and if anybody is going to sell a slave, that’s the time they do it; and if anybody’s going to give away a slave, that’s the time they do it; and the slave never knows where he’ll be sent to. Oh, New Year’s a heart-breaking time in Kentucky!”

Clarke’s account is an American truth, as historically relevant as those stories that Morgan and many other Republicans might prefer we continue to center on this and every day. It’s a history that Morgan wants to be whitewashed until it fades from collective American memory. But it’s critical that these stories—which tell us how we arrived at the present moment, and why we can’t seem to ever get beyond the residual impact of a past Morgan would like to forget—be told.

There’s an old Black saying, borne of Hiring Day, that states New Year’s will define your coming year.

“Slaves went to a place [on Hiring Day] called the hiring grounds to hire their labors out for the next year,” Sister Harrison, a formerly enslaved freeperson told an interviewer in 1937. “That’s where that sayin’ comes from that what you do on New Year’s Day you’ll be doing for the rest of the year.”