Charisse JonesUSA TODAYhttps://imasdk.googleapis.com/js/core/bridge3.435.0_en.html#goog_978138837

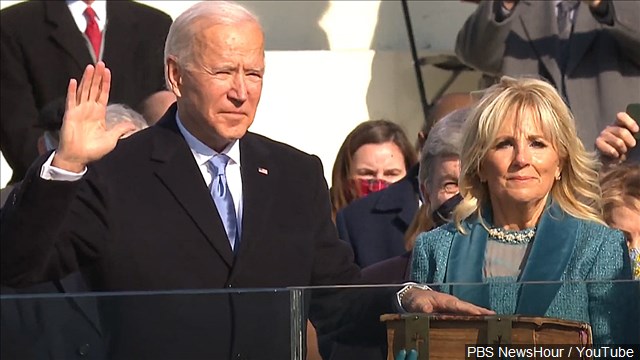

A key pledge in President Joe Biden’s plan to build the nation “back better’’ is to be bolder in addressing the systemic racism that has hindered the advancement of Black Americans, and other people of color, for generations.

The pursuit of racial and economic justice informed the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose birth is being celebrated in a national holiday Monday. And along with health care disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the police abuse brought to light by the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless other African Americans, economic inequality is front and center in the national consciousness.

“These crises have ripped the blinders off the systemic racism in America,” Biden said of COVID-19 and the nation’s struggling economy in written remarks delivered Dec. 11, when he announced nominees to his governing team.

“The Black and Latino unemployment gap remains too large,” he continued. “And communities of color are left to ask whether they will ever be able to break the cycle where in good times they lag, in bad times they are hit first and the hardest, and in recovery they take the longest to bounce back.”

Biden’s proposals include boosting lending to entrepreneurs of color; creating and restoring parks and infrastructure in Black, Latino and indigenous communities; and empowering the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to more forcefully root out discrimination in the workplace. He will take office Wednesday.

Biden’s plan for COVID aid:Here’s how a Biden stimulus plan could impact wages, stimulus payments and unemployment checks

A nation divided:As Biden prepares to take office and America reels from Capitol riots, Black and white still define the nation

But the challenge of narrowing a racial gap that spans areas from homeownership to wages to property taxes is vast.

While the Biden-Harris administration has outlined “solid proposals” to challenge some economic inequities, to significantly “rectify racial and socioeconomic disparities that exist within Black communities, they need to address the root causes of these issues,” says Arisha Hatch, vice president and chief of campaigns for the racial justice group Color Of Change.

“With the systemic racism that has locked us out of job opportunities, education, and access to health care,” Hatch said, “it’s going to take more than well-intentioned plans to close the racial wealth gap for Black communities.”

Black homeownership: Lowest level in 50 years

An array of policies, practices and in some cases, outright violence, have impeded the ability of African Americans to own, or hold onto, their own homes, a key asset for building wealth.

In 2019, homeownership among whites stood at 73.3% compared with a homeownership rate of 42.8% among Black households, the widest gap since 1983, according to Harvard University’s State of the Nation’s Housing 2020 report, sponsored by Habitat for Humanity.

The economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic may make that disparity even greater.

While 36% of homeowners lost pay from March through September, 41% of African American homeowners saw a drop in income according to the Harvard report, citing data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. And at the end of September, 17% of African Americans who owned a home were behind on paying their mortgage versus 7% of whites, the report said.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed housing discrimination. But “these barriers continue,” says Kilolo Kijakazi, an Institute Fellow with the Urban Institute, a think tank focused on economic and social policy.

Homebuyers of color, for instance, were frequently steered toward high-interest subprime loans that are more difficult to repay, even when those same customers qualified for more affordable lending options. That left them more vulnerable to potentially losing their homes.

The subprime lending crisis contributed to the Great Recession that began in 2007.

“African American homeownership is at the lowest level that it’s been in 50 years in part due to some of the loss incurred after the subprime lending debacle,’’ Kijakazi says.

Lack of homeownership creates a domino effect, depriving families of assets to hand down, and equity that can be tapped to seed a business, pay for unexpected expenses like medical care, or to fund higher education.

“If you’re Black and your parents didn’t own a home, you’re more likely to take out loans,” says Andre Perry, a senior fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings, and author of “Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities.” “So wealth begets wealth. But a lack of wealth also begets debt, and that’s what’s happening all across the country.”

Destruction and theft of property

And then there was theft. In perhaps the first documented theft of Black people’s property, Virginia’s 1705 law took and sold off possessions belonging to “any slave,” and the profits were directed to benefit “the poor,” according to “Stamped From The Beginning” by anti-racism scholar Ibram X. Kendi.

“The story would be told many times in American history,” Kendi wrote. “Black property legally or illegally seized, the resulting Black destitution blamed on Black inferiority, the past discrimination ignored when the blame was assigned.”

In the 19th and early decades of the 20th century, white mobs frequently attacked and destroyed thriving Black communities.

“Greenwood, Rosewood… the reality is that was going on all over the United States,” Perry says of communities in Oklahoma and Florida that in 1921 and 1923 experienced two of the most infamous episodes of such destruction.

The Tulsa massacre, which destroyed that city’s all-Black Greenwood District, began after a 19-year-old African American man, Dick Rowland, was accused of allegedly attempting to rape a 17-year-old white elevator attendant, Sarah Page.

Goaded by articles in the local newspaper, and likely fueled by white resentment of the success and affluence of the district known as “Black Wall Street,” whites descended on the community of roughly 10,000, burning 1,500 homes to the ground and bombing more than 600 Black-owned businesses, according to the Tulsa Historical Society.

Thousands were left homeless, and personal property and financial losses and damages totaled over $2 million, including cash some residents kept at home because they didn’t trust white-owned banks.

Two years later, a days-long massacre destroyed the Black community of Rosewood, Florida, as an alleged attack of a white woman by a Black man spurred mobs to torture and murder African American residents and burn the town to the ground.

In more recent decades, so-called urban renewal efforts that officially set out to revamp blighted pockets of cities often stripped Black Americans of their property without sufficient compensation.

For instance, eminent domain was used starting in the 1960s to clear more than 500 acres in the predominantly African American southwest section of Washington, D.C., uprooting 1,500 businesses and displacing 23,000 mostly Black residents, according to a paper co-authored by Kijakazi.Will Kamala Harris as vice president finally change how corporate America sees and treats Black women? Stimulus checks: There’s a new round of scams, too. Here’s how to avoid them Three signs your money management skills need an overhaul Trying to pay off debt? Here are 4 mistakes to avoid when doing that. The Daily Money: Subscribe to our newsletter

Redlining now outlawed

Redlining, a discriminatory practice that prevented Black homebuyers from getting mortgages, also left many Black neighborhoods depleted.

While redlining is now outlawed, underinvestment in Black neighborhoods continues, Perry says. And the new building and restoration that comes with gentrification often result in Blacks being displaced, unable to afford higher taxes or rents, as more affluent whites move in.

“You’d be surprised how much destruction you can do with tax policy,” Perry continues, “by selling off land to developers without consideration of the Black communities around them. It can absolutely devastate a community like a bomb.’’

Overtaxed: Blacks pay more property taxes

In 1910, it’s estimated that African Americans owned up to 16 million acres of land. Today, they own under 5 million acres, says historian Andrew Kahrl, a professor at the University of Virginia who has extensively studied African American landownership.

Based on Black population numbers in 2020 as compared with 1910, the average Black American owned 14.5 times more land a century ago than they do today, according to a USA TODAY analysis.

One reason for that staggering loss is property taxes, which, at times, have been used overtly to strip African Americans of their property.

“A lot of this was very subtle” Kahr saysl. “Many African American landowners didn’t know they were being overtaxed… But over time, it added up to being a very heavy burden with long-term consequences for Black wealth-building and economic mobility.’’

During the time of “Jim Crow,” when segregation and discrimination against Black Americans were enshrined in local and state laws, white landowners in the South, particularly those with a large amount of property, would often be given unreasonably low assessments, and local officials would shift the tax burden to smaller, often African American landowners.

“It’s putting your thumb on the scale for white landowners,” says Kahrl. But additionally “it was part of a larger philosophy of taxation that guided Jim Crow policy in general and is a part of our politics today … A philosophy of taxation that tried to sock it to the poor, the Black poor in particular, out of a sense that they weren’t deserving of the benefits of those tax dollars to begin with.’’

The discrimination could be blatant. In 1967, white officials in the town of Edwards, Mississippi, doubled the assessed value of most homes owned by African Americans to punish Black residents who were protesting the town’s continuing discrimination.

But even if bias is unintentional, structural issues continue to put Black taxpayers at a disadvantage.

Today, Black and Latino residents pay 10% to 13% more in property taxes than their white counterparts, according to a paper published in June by Carlos Fernando Avenancio-León of Indiana University and Troup Howard of the University of California, Berkeley.

That may be due in part to a history of segregation and underinvestment in communities of color. Assessments are based on the perceived market value of a home, and tax officials may factor in a house’s number of bedrooms or size, but not whether it’s located near a park or highly regarded school, features that can inflate a home’s worth.

Because Black neighborhoods are less likely to have amenities like parks or highly regarded schools, even a white owner’s home would be less valued in a Black neighborhood.

And Black and Latino homeowners – who appeal their assessments less, win those appeals less often, and see smaller tax cuts than whites when they are successful – tend to pay higher property taxes wherever they live. Lack of access to lawyers, and a reluctance to trust and challenge the official process are some of the reasons.

Bias on the part of potential buyers also plays a role.

“The same property in the hands of an African American, or located in a predominantly Black neighborhood is going to be devalued because of its location” or the race of its owner, says Kahrl, who was not involved with the Indiana University and U.C. Berkeley study. “Invariably, it means the assessment is at a higher percentage of market value than white-owned property.”

The pay gap: Blacks paid less than whites

In 2016, the net worth of a typical white family was $171,000, almost 10 times that of an African American family, which typically had a net worth of $17,409, according to Brookings.

While wealth involves assets that go beyond weekly wages, income plays a significant part, and Black Americans on average are paid less than their white peers, no matter their profession or education.

Recent census data reported that the median income for white non-Hispanic households was $76,057 in 2019, a 5.7% increase over the previous year, and an 8.2% increase since 2000.

The median income for Black households saw a steeper spike – 8.5% – in one year. But it hovered at $46,073 in 2019 and had crept up just 1.4% from where median income was in 2000.

“There are barriers in the labor market that further contribute to the gender and racial wealth gap,” says Kijakazi, who added that African American workers also experience higher rates of joblessness at every level of education. “Racial discrimination in hiring has persisted despite the enactment of legislation.”

Black men on average make 71 cents for every dollar paid to white men, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Black women, meanwhile, earn 63 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men. That adds up to a loss of $24,127 a year for Black women, or $965,078 over the course of a work-life spanning 40 years, according to an analysis by the American Association of University Women.

Lower wages, longer gaps in employment, and jobs that are less likely to offer pensions or savings plans like 401(k) plans also impact how much income people have to carry them through retirement.

“African American seniors are less likely to have financial assets, retirement accounts, and home equity than white seniors,” says a July 2019 paper, “African American Economic Security and the Role of Social Security,” that was co-written by Kijikazi.

Remedies to root out systemic biases

Despite entrenched beliefs in race, there are ways to root out systemic biases, experts say.

“We created these concepts to suppress, we can create new concepts to create inclusion,” Perry says. Black Americans “are over-policed. We are discriminated against in the job market. These things you can correct, and it will help change the perception of people of color.”

Remedies to bridge the wealth gap can include measures like federal job guarantees, in which any adult who wants a job can get one from the government, higher taxes on wealth versus income, and the introduction of trusts known as “baby bonds,” economists, civil rights advocates and lawmakers say. Such initiatives would also have an impact on lower-income families regardless of race.

Conceived by the economist Darrick Hamilton, baby bonds would be federally funded accounts set up for every child born in the U.S., with larger contributions given overtime to those in poorer families.

In July 2019, Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and Representative Ayanna Pressley, D-Mass., reintroduced the American Opportunity Accounts Act, which would start every newborn with $1,000. Each child would receive up to $2,000 more each year, based on their family’s earnings, and at age 18, he or she could tap that money to buy a home or pay for higher education.

The Biden administration also has some promising initiatives, says Hatch of Color of Change. They include improved access to credit that could help narrow the racial wealth gap, and making sure that half of new funds allocated by a federal Paycheck Protection Program go to businesses with no more than 50 employees. That could be especially helpful to Black-owned businesses, the majority of which are solo ventures or employ no more than two people.

“Our priority will be Black, Latino, Asian and Native American-owned small businesses,” Biden said when announcing his economic and jobs team on Jan. 8. “We’re going to make a concerted effort to help small businesses in low-income communities, in big cities, small towns, rural communities that have faced systemic barriers to relief.’’

Still, more far-reaching measures, like federal business grants and a higher minimum wage are also necessary, Hatch says.

“What we need from the Biden-Harris administration is a federal jobs guarantee, an influx of affordable housing, a higher federal minimum wage, and much more,” Hatch says. “If Black communities are going to survive this crisis, we need the new administration to act with the urgency this moment requires.”

Biden has said he is hopeful it will be easier to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour now that Democrats control Congress in the wake of Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff winning the recent Georgia runoff elections for two seats in the Senate.

With such initiatives, race could perhaps become less of a barrier and more of a marker to measure progress and change.

“You can’t create a whole society based on race and then” just stop, says Deena Hayes-Greene, co-founder of The Racial Equity Institute. “We have to take account of race until we change the structure that perpetuates these differences over and over again. Then we can stop checking the boxes.’’

Contributing: Jayme Fraser