by Orissa Arend

Local organizing coalition Justice and Beyond (J&B), Ashe Cultural Arts Center, and the National African American Commission on Reparations joined forces on March 12 to assemble a powerful day-long town hall meeting on reparations for African Americans in New Orleans. J&B is a Black led organization. Its forums are designed to lift up the voices and concerns of people of color in New Orleans. It is not led by one or two people but by a group of “pillars” representing “pillar organizations.”

I am a pillar. My job, as one of the small number of white pillars, is to take the concerns and activities of J&B back to my organizations – Trinity Episcopal Church and Community Mediation Services. We white pillars are more than tokens or gofers. We are respectfully included in the decision-making and implementation of all aspects of J&B governance.

Lessons Learned

I’ve learned a lot over the 8 years of my involvement with J&B. It’s not the easiest for a white person – or at least not for ME – to sit back and take direction, to not be bossy and question everything. But in the learning department, I got more than I bargained for when J&B took the leap from weekly zoom pandemic forums to an all-day in-person town hall for 100 people. It had national reparations activists, local grass-roots experts in housing, culture, health, and restorative justice and a dazzling array of cultural sharing through song, film, and original theater.

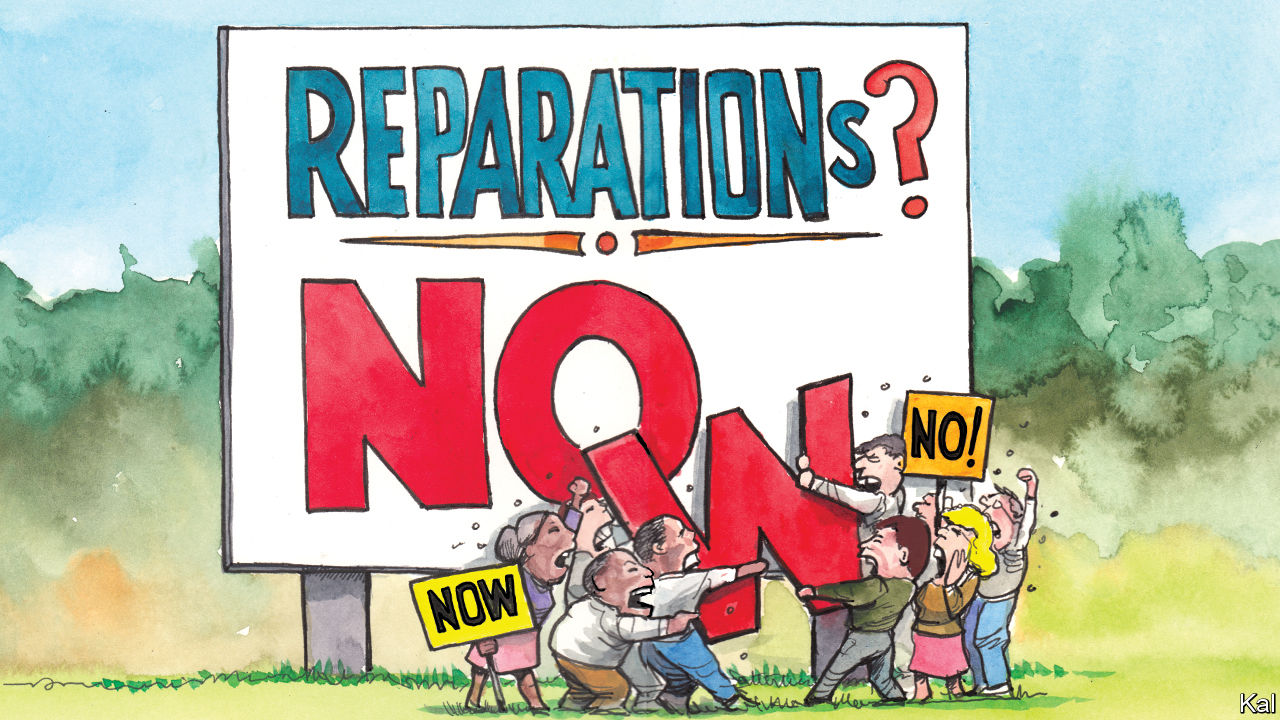

Remember, this is a white girl’s reflections on reparations. The first thing I learned is that reparations means many things to many people. To some it means a check to make up for slavery. Ridiculous! Right? What could make up for slavery? Any amount would be way too little and way too late. Best not to dwell on it and move on. That’s the temptation. I hear that a lot. Lead us not into temptation. But deliver us from the evil of repeating our mistakes.

Some institutions – I’ll use mine, the Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Louisiana, as an example – are finally acknowledging complicity in the historical sin of racism. They are cataloging specific harms, and exploring ways to make amends. I’ll spare you the list because it is long. But it includes our first Bishop, Leonidas Polk enslaving 200-300 people on his sugar plantation. The Church itself twisted the liberating message of the gospel “to uphold a society profiting from the labor of enslaved persons” (from a statement of our Bishop Morris Thompson on Reparations). More recently, Episcopalians set up schools for privileged white children whose parents deserted public schools after school desegregation.

How do you define reparations?

Reparations can be monetary. The Dean of Virginia Theological Seminary spoke recently at Trinity Church to explain their reparations program which allots an annual amount to the descendants of those held in bondage and sometimes sold to run the seminary. The Dean explained that the rationale was both practical and theological. Pay people fairly for their work; and wealth sould be allowed to accumulate and passed down through the generations.

Theologically, each of us in the Episcopal Church takes a Baptismal vow to “strive for justice and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human being.” Again, from Bishop Thompson’s statement, “Collectively, we as the Church have fallen short in our fulfillment of this basic tenet.”

Reparations can take the form of money, services, programs, an apology, and many other forms of assistance. It can be collective or individual. And the harm goes way beyond slavery to the many aspects of racial injustice which continue to this day, we learned at the town hall. But the form of reparations should be determined by the victims of the harm, we also learned. Sometimes young people and their elders disagree about what is needed for repair.

This is a white girl’s reflections on reparations.

We know that our next steps are to document the harms for African Americans in New Orleans stemming from enslavement, slave trading, legalized racial discrimination, and economic exclusion. The New Orleans Data Center can help with this. Then we create a narrative based on data explaining the disparities. The City Council could then establish a Reparations Task Force and a Community Reparations Fund controlled by locals with a track record of effective grassroots work.

Related: Reparations for New Orleanians

The town hall touched us on many levels, not just in the head. In the play created especially for the town hall meeting, and directed by Asali Ecclesiastes, OT (aka. Oliver Thomas) laments to Mama NOLA, (channeled by Kathy Randels): “Mama, it’s trauma on top of trauma on top of trauma on top of trauma.” Later, he says, “If you keep starving one baby to fatten up another baby, the baby you starve is gonna get sick and DIE! We need reparations Mama. Been needing them for 400 years. Lied to about getting them 150 years ago. And every time it comes up again, y’all find something else to talk about. Some other cause to give to. Reparations is on the table, and we not taking it off until they are paid, Mama!”

Some in the audience took issue with Mama NOLA being a white woman, arriving from France with the casket girls to be the brides of French settlers. “Shoot,” she says, “Landed in a nasty swamp, several degrees south of the one I was born and raised in, and they put me in a damn habit, tried to train me to be some stinky French Man’s slave for the rest of my life. Never seen so many mosquitoes in my life; and roaches? That fly?”

Mama NOLA is ancient, wise, shrewd, tipsy, sexy, and sees herself called to take care of ALL of her New Orleans babies. OT challenges her to some serious soul searching that involves the ancestors. For the conversation in the play to occur, Mama would have to be mighty white. The play will be performed again at the Tennessee Williams Festival on Sat. March 26. You can see it and talk back afterwards. Here is the link for tickets: https://tennesseewilliams.net/events/reparations-with-ot-and-mama-nola/.

One comment that stuck with me about the town hall was from my friend Robert King, a Black Panther who spent 29 years in Angola State Penitentiary in solitary confinement as a political prisoner. We owe him reparations big time. He brought Freelines, the candies he perfected in his 6 by 9 foot cell, to give away. He said, “The haters, the people who hate Black people just for the color of their skin – they have a serious mental disorder that also needs repair. If we look at reparations too narrowly, we miss the fact that we don’t live in a democracy. If we did, reparations would extend to everyone.”

The town hall gave all of us have much to ponder and act on.