Watching Court on a Monday Morning

By Orissa Arend

On Monday mornings I step into a completely unfamiliar world – the criminal courthouse on Tulane and Broad. I am a volunteer court watcher, trained to observe, assess, and report all that goes on in the courtroom — things like fairness, efficiency, transparency, and treatment of victims and children. Each court room is its own little fiefdom, with its own rhythm and vibe.

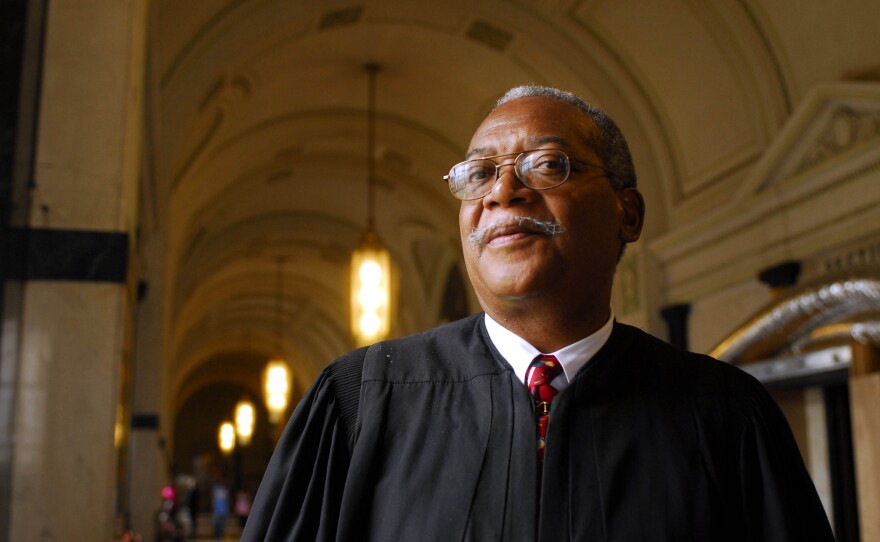

This morning I’m sitting in Judge Calvin Johnson’s court. He’s the substitute judge until newly elected Judge Simone Levine, formerly the director of CourtWatch NOLA, returns from some kind of a judge conference at Destin beach. I’m wearing one of my two outfits that I think makes me fit in with the lawyers. Black or navy blue. But I can’t go as far as high heels.

A Day at Criminal Court in New Orleans

Judge Johnson starts with a Langston Hughes poem. His kind, broad smile and his tall, dignified demeanor bring all of us into the unity that the poem expresses. All of us – prisoners in orange suits and handcuffs and their guards, the hard-working, ever cheerful court reporters and clerks, the lawyers, and the on-lookers who are interested family, friends, or victims of the defendants.

Judge Johnson’s demeanor contrasts with some of the other judges whose demeanor is imperious. Once, to my horror, I was so engrossed in studying the docket — the ledger that tells us who is accused of what and where the case sits in the multi-step legal process — that I didn’t hear “All rise” when the judge walked in. I didn’t rise. The judge, appropriately, called me out in a big way.. There I was, with my little yellow CourtWatch lanyard, trying to look inconspicuous. And I had to wait until the end of court to apologize. (The judge gave me a reassuring hug.)

The docket has things like murder, domestic abuse, child endangerment, theft, aggravated assault with a firearm, burglary. It reminds me of things I’ve done that could have gotten me arrested – slipping makeup into my purse in a department store when I was a teenager; kicking in my ex-husband’s door to try out my karate skills because he wouldn’t talk to me. Times when white skin privilege came in REALLY HANDY. Judge not, my scriptures tell me, that ye be not judged.

A Day at Criminal Court in New Orleans

About three quarters of the way through the docket I notice that 14 little boys – ages 9-13 – have noiselessly slipped in behind me. They are wearing blue jeans and red T shirts that say “Don’t Stop Dreaming.” I learn that they are a sports team whose augmented activities are financed by Norris Henderson, director of VOTE, Voice of the Experienced. Norris spent many years in Angola State Penitentiary. Besides coming to court, the boys were going to Baton Rouge to talk to Royce Duplessis and the legislature, and to Whitney Plantation. Another day was set aside for the boys to feed the homeless. Their coach seemed to know a good number of people in the room. He had either coached them or their kids.

Related: Fixing Criminal Justice in New Orleans

Judge Johnson invited the boys to sit in the jury box so he could see them better. And when court was finished for the day, he spent an hour talking to them and answering their questions. Oh those questions! After every answer five more hands shot up. There was just SO much the boys wanted to know! Judge Johnson opened with asking about their dreams – the dreams that didn’t involve sports –to be president, to get rid of poverty, to become a judge. Judge Johnson inserted a reality check by asking a boy how many years of education it would take to achieve his dream and was he willing to commit to that.

A Day at Criminal Court in New Orleans

“What made you want to become a judge?” one youngster asked. Judge: “Do you want the text book answer or the real one?” You can guess what they wanted. Judge: “I got arrested when I was 15 for inciting a riot. I was prosecuted and convicted. I was put on probation. Lolis Elie was my lawyer. Right then I decided I wanted to be a lawyer and a judge.”

Another child said, “When I saw the handcuffed prisoners here, it reminded me of slaves. What is the connection?” I thought, damn, he must be reading the book I’m reading, Clint Smith, How the Word is Passed. Smith explains that after the Civil War, convict leasing was even more violent than slavery because it didn’t matter to the bosses if the workers died. No loss of property. Every one replaceable. Slavery was made legal if you were convicted of a crime. It still is in Louisiana.

The Judge complemented the young man for his grasp of history. He explained that enslaved people were punished and shackled for nothing, whereas prisoners were shackled because our legal system has found them guilty of a crime. Or in some cases, just accused and they can’t make bail.

“What do you think when you walk into the courtroom?” one youngster wanted to know. Judge: “My goal is to make sure everything I do here is right.”

To close out the day, the Judge had a child step up to the mic and read the Lanston Hughes poem The Kids in School with Me. When the child stumbled over a word, the Judge joined in – smooth and unobtrusive.

That was my day in court.

Excellent article! I have a sort of “Perry Mason” like interest in criminal proceedings and justice. How does one get involved as a volunteer in CourtWatch?