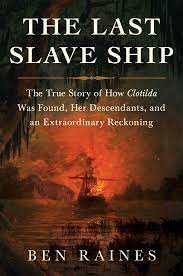

by Orissa Arend

The Last Slave Ship by Ben Raines (Simon and Schuster,2022) is a true story. It begins with the fatuous bet by an Alabama plantation owner. He claimed it would be easy to evade the international slave blockade. That led to the construction of the slave ship Clotilda. The subsequent voyage brought 110 captive Africans to Mobile Bay 50 years after the horrific trade was outlawed. It traces Cudjo Lewis’s capture as a 19-year-old from his idyllic life as a Yoruba villager in the land of plenty by Dahomean soldiers from a nearby African village. The tale goes from there to Africatown, the Alabama community founded by Clotilda captives after Emancipation. The town prospered in the Jim Crow South!

Related: American Reparations

We have the story in Cudjo’s own words because anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston interviewed him and wrote about it. She moved to Mobile in 1927 and visited Kudjo at home multiple times a week. She even took pictures. Kudjo was 87. He was the last survivor of the captives who founded Africatown. And he was the last person alive who had experienced the Middle Passage.

The stories of the enslavers are also so well researched that you feel like you are there, for the mutinies, the storms at sea, the chases by patrol boats, the burning and sinking of the Clotilda to destroy the evidence, and the ferocious resistance of the Africans once they arrived at plantations.

After 5 years of slavery, which ended with the Civil War, the Clotilda Africans demanded reparations, land to build their very own town on. They could organize because they stayed connected and kept their language. They were community-minded and hard workers. Their enslavers, of course, wouldn’t consider giving land. In fact, they felt that THEY were owed reparations for their loss of human property!

Related: Reparations in New Orleans

So the Africans came up with Plan B – go back to Africa. Too expensive, they decided, and no telling what they would find back home. Plan C – work hard, pool money, and buy the land themselves for their town. Which is what they did. Illiterate themselves (in terms of English), they built a school and hired teachers for their children. Becoming Christian (with some Vodun mixed in) and not wanting to go to the churches of their oppressors, they built a church. They built houses and figured out a system of governance and conflict resolution.

To quote the author: “They suffered through racial violence, murder, disease, and betrayal by people they trusted. All of this in what was then the nation’s most intensely racist state. There the wheels of government continually sought new ways to suppress them. But the Africans did not shrink or hide away among themselves. Of course, they had branded themselves as fighters from the start, from the moment they stole the overseer’s whip and lashed him with it in Meaher’s field [the plantation owner and financier of the Clotilda]. Everything that happened after that was just a continuation of that first impulse – to fight, fight for their lives, their rights, their future, and their children.”

But then in the 1960’s and 70’s and beyond, the town was ravaged by the same forces that destroyed so many African American communities – industrial pollution, highways, crack cocaine, and opportunities to move and shop elsewhere. According to the author, who is an environmental journalist, Mobile thinks of Africatown as a dumping ground for dirty industry even today. The atrocities and lack of regulation he cites sound exactly like the African American struggles in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley (aka Death Alley).

RECONCILIATION

From the book flap: “To this day, Clotilda is a ghost haunting three communities: the descendants of those transported into slavery, the descendants of their fellow Africans who sold them, and the descendants of their American enslavers. This connection binds these groups together.”

In 2019 when the ship was found by the author who is a diver and charter boat captain among other things, 160 years after it had been burned and sunk, there was renewed energy for apologies and for healing. The Mobile family which commissioned the Clotilda, the Meahers, had gotten rich off of slave labor. Their descendants were significant players in the local real estate market at the turn of the 20th century. And they did their best to disenfranchise and impoverish residents of Africatown. To this day, their descendants refuse to be quoted about the Clotilda and have accepted no responsibility for the deeds of their forebears, afraid that their family will be sued for kidnapping.

But apologies between Africans and African Americans did happen. Hector Posset, Benin’s ambassador to the United States, came to Mobile and performed a Vodun ritual on the author’s boat on the backside of Twelve Mile Island, where the ship lies, tears streaming from behind his sunglasses. This is what he said: “I am a prince of Dahomey. It was my father’s ancestors who did this. But my mother was Yoruba. Her ancestors came here to this country forcibly, they didn’t choose. And it was my father’s family who sold my mother’s family. This is why I wept. . . we sold our people. Brothers sold their brothers and sisters. Fathers sold kids and wife. I will never blame those who came here. I will always beg them for forgiveness.”

Jason Lewis, who grew up in Africatown, speaks for the diaspora, “Whoever did what back with the slaves, here in Mobile, or in Africa, they have a chance to say, ‘I apologize for what my great-great-grandfather did.’ And then we as the diaspora, we have a chance to say, ‘We forgive you.’ But with Clotilda, we have a chance to say it on a world stage, where everybody knows this is the last ship to come in, and we have a chance to have the actual descendants of the people who perpetrated it. . . to come together and tell the world they forgive each other.”

Enter Michael Foster, a retiree from Great Falls, Montana who had heard about the Clotilda and figured out from an Ancestry website that his great-great-great grandfather was captain Foster’s brother. Foster sailed the ship to Africa through 4 mutinies, several storms, and patrol boat chases where he nearly thew his human cargo overboard to avoid being hung for illegal slaving. He resented the fact that he never got the credit he thought he deserved.

When Michael Foster decided to come to Mobile to apologize to the Clotilda descendants, he told the author: “I just don’t know what to expect. Are they going to hate me? Will some of them yell at me? It’s a bad thing that was done to their ancestors. I don’t know what I can do but say I’m sorry.”

“That’s exactly what they want to hear,” the author told him. “I think you will find an incredibly warm reception. All they talk about is reconciliation. They want to forgive.” And that’s what happened. I like to think that no matter what the reception, Michael Forster would have gone ahead with the apology anyway.

SOME QUESTIONS FOR US

Can anyone read this book and not see the need for reparations? An apology is often an important part of that. Think Calvin Johnson and the recent apology from Governor John Bel Edwards 60 years after being arrested for inciting a riot while peacefully protesting for his civil rights. Are we really so disconnected from our ancestors that we won’t work to heal the generational guilt and trauma festering as a result of sins of the past? Without the hard work of reparation, sins of the past become sins of the present. Do we have the will and the courage to break that devastating chain?