The “new normal” of the U.S. economy is sending shockwaves across companies’ bottom lines as owners and managers struggle to staff up.

“The U.S. is experiencing a labor shortage, especially in the labor and hospitality sector,” says Daniel Zhao, a senior economist at Glassdoor, a job and recruiting site.

Republican elected officials and some business owners blame the labor shortage on Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PAU), a federal subsidy that pays an extra $300 per week in unemployment benefits.

“The most vocal source of speculation [for labor shortages] is that the supplement to weekly unemployment benefits is enticing a lot of people to stay home,” said Erica Groshen, a labor economist at Cornell University and a former commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics during the Obama administration. “I think that’s far too simplistic,” he told CNBC.

At least 25 Republican-led states believe the benefits are keeping people home, so they’re opting out of the PUA three months before the program expires to force workers to return to the workforce.

Also, a handful of the states are offering return-to-work bonuses of up to $2,000 in place of the enhanced unemployment benefits, though there are caveats like limited availability.

New Orleans businesses are also feeling the pain of staff shortages.

“We could easily hire 20 to 24 people today. I need them,” Drago’s owner Tommy Cvitanovich told Fox 8. Cvitanovich thinks some people are making more on unemployment than they can on the job.

“At the end of the day, $547 a week is too much. People stay home, and we have to compete against that,” said Cvitanovich.

Metro Services Group co-founder and CEO Jimmy Woods, Sr. says his company needs at least 20 drivers with CDLs (Commercial Driver License) and two years of experience. “We’ve probably lost eight to nine drivers to our competitors,” Woods explains. Metro’s competitors are paying drivers more than Metro can pay. “We’re in a bidding war,” he adds. And Metro’s ability to pay their drivers is locked into an outdated contract with the city. Static wage rates are baked in the contract. So Metro has little to no wiggle room.

New competitors in the metropolitan area, in Jefferson, and other parishes are driving salaries up. Also, the pandemic prompted some employees to leave the company and start businesses.

Metro pays drivers from $15 to $21 per hour, depending on experience. Hoppers earn at least $11.40 per hour.

“That’s not the ceiling of what we pay; that’s the base. Most make more than that!”

Jimmie Woods – Metro Disposal

RELATED: GROWING PAINS FOR METRO DISPOSAL

The entrepreneur says the company’s contract with the City of New Orleans is one reason for Metro’s inability to pay a living wage. In the fourth year of its seven-year contract, Metro’s $13 per household bid for three visits to each home per month is not enough to offer higher salaries.

The company has had to pull drivers from its other companies to fill the labor gap. “We have to import CDL drivers every week for ten days at a time and put them up in hotels to meet contract requirements.”

Metro is losing money. In the past, Metro got a royalty for picking up recyclables. Now, the company pays to dispose of the materials. “When China pulled out of the program, the bottom fell out of the recycling market.”

Woods says he’s continuing to push through and look for innovative ways to bring CDL drivers aboard. Of those who have stuck with him through hard times, Woods said, “I tip my hat to our workers. I can’t thank them enough.”

Are New Orleanians willing to pay higher water bills to account for the new economics surrounding trash collection? A $10 per month increase would allow the city to pay garbage contractors more. Doing that stops the collection gaps.

Also, pandemic lockdowns might be partly to blame for the labor shortage. But a wage reckoning by workers who refuse to return to jobs paying poverty wages could be the primary cause of the hiring shortfall.

Economists the federal minimum wage of $7.25 is not a living wage. Even a person earning $15 an hour is only grossing about $31,000 annually. That’s not enough to purchase a home in the suddenly gentrified New Orleans real estate market.

“The median necessary living wage across the entire U.S. is $67,690. The living wage in Louisiana is $63,842,” Business Insider reports.

The “living wage” is defined as the income you need to cover necessary and discretionary expenses while still contributing to savings. Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the 50/30/20 budgeting rule — which allocates 50% of your income to necessities, 30% to discretionary expenses, and 20% to savings —GOBankingRates published a study of each state’s living wage.

“Most Americans live paycheck to paycheck. So once the pandemic hit, many didn’t have any savings to fall back on. Conservative lawmakers complain that the extra $300 a week unemployment benefits Congress enacted in March discourages people from working now. What’s really discouraging is the lack of childcare and lousy wages,” economist Robert Reich wrote in The Guardian. “Essential workers deserve far better.”

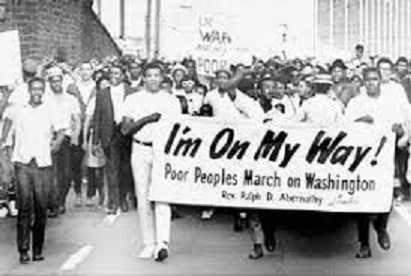

Americans’ fight for good-paying jobs is decades old. From the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs to the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign led by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the re-launch of the Poor People’s Campaign in 2018 led by Rev. Dr. William Barber, II, to the nine-year-old fight for $15, workers have continued to march and demand living wages.

Feeling the pressure of workers’ demands and strikes, a few multinational corporations, including Amazon, Costco, Target, and Best Buy raised salaries to $15 per hour, even before the pandemic hit.

But workers’ demands fall on deaf ears in Congress. However, if the Senate passes SB1, $15 per hour becomes the federal minimum wage.

The pandemic has caused a paradigm shift in the fight for living wages. The labor market will never be the same. People are starting businesses, returning to school, and finding other ways to earn a living wage.

Reich, a former U.S. secretary of labor and professor of public policy at the University of California at Berkeley, offers advice for returning the labor market to normal:

“Workers are always essential. We couldn’t have survived without millions of warehouse, delivery, grocery, and hospital workers risking their lives. Yet, most of these workers are paid squat. Most essential workers don’t have health insurance or paid leave.”

‘The Stock Market isn’t the economy. Stop using the stock market as a measure of economic wellbeing. Look instead at the percentage of Americans who are working and their median pay.’

Working people know the truth and facts. The daily highlight of the stock mart is a joke. People are sick and tired of working for wages that can’t even sustain the cost of living. Bad managers and bad customers are driving people to work outside of service industry because people of these factors to. The GOP with that UI rhetoric is just recycled propaganda and media needs to stop giving them the mic!