Moving the Goal Posts: Cognitive Dissonance and Preferences

- In cognitive dissonance theory, people experience mental discomfort when acting or espousing views conflicting with starting preferences.

- To minimize or avoid pain or discomfort, persons can change their preferences to align more closely with their actions.

- Research indicates that making a choice or undertaking an action, even blindly or on a whim, can lead to an increased preference for that choice.

- Preferences or principles once thought to be fixed, or “immutable” are subject to change in political settings and scenarios.

Cognitive dissonance theory posits that individuals experience mental discomfort after taking actions or espousing views that appear to be in conflict with their starting preferences.

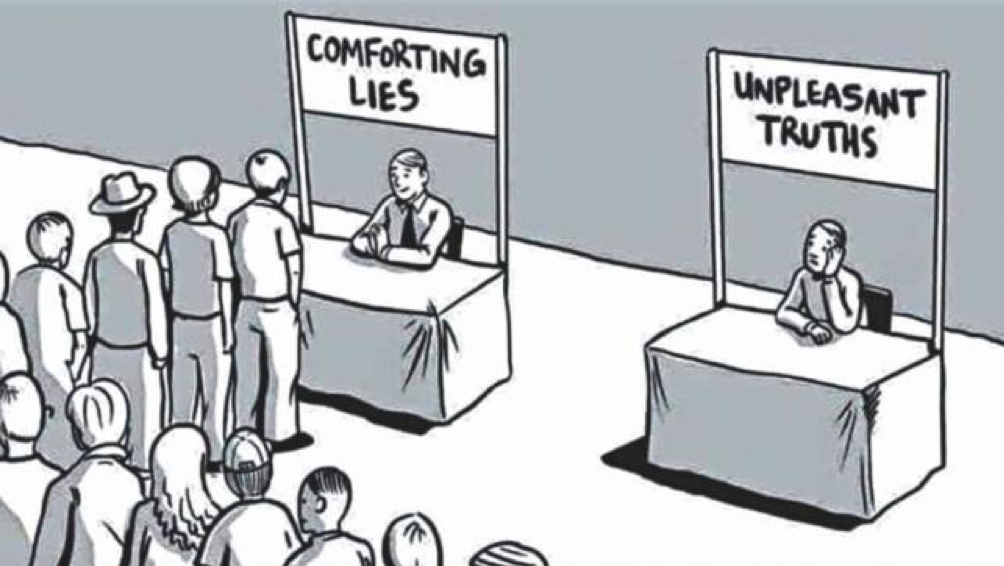

To minimize this discomfort, they can change their preferences to align more closely with their actions. In other words, folks can move the goalposts so that they are safely ensconced in a new “discomfort-free zone.”

Recent research indicates that making a choice or undertaking an action (e.g., voting for an unorthodox candidate), even blindly or on a whim, can lead to an increased preference over time for the chosen alternative and a devaluing of other options (Acharya et al., 2018).

This can lead to polarization over time, as witnessed by everyday comments on FaceBook, Twitter, and, curiously, LinkedIn: “I support hard right candidates because everyone else is a stinking socialist,” or “Sure, my candidate sounds a bit bigoted, but he or she just tells it like it is.”

Once they have made their choice, people can rationalize anything and tend to double down over time, no matter what. This is why young folks who choose Republican or Democrat tend to stay with that political affiliation for a lifetime. This explains stability in political views and affiliations.

What explains a drift in preferences and principles?

Maya Sen, a Harvard political scientist, infuses social psychological principles into cognitive dissonance theory and applies them to political scenarios and settings. Positive political theory traditionally has focused on rational choice approaches wherein action choices stemmed from immutable preferences.

But Acharya et al. (2018) suggested that this may not be the case. Here is a hypothetical scenario: What would the party out of power say if the leader of the party currently in the White House was found to have top secret, highly classified documents in unsecured locations? What if the current leader’s time in office ended and then this happened?

Based on politicians’ preferred discourses of nationalism, national security, and law and order, it is reasonable to assume that the opposing party would be positively apoplectic. They’d cry “treason,” accuse him or her of espionage, and contemplate various severe punishments. However, if it was their leader who was being investigated in this scenario, cue the stratagems for handling the ensuing cognitive dissonance.

In response to the mere possibility that their leader might have done something highly illegal, every possible rationalization and ex post facto excuse would be floated. Ever-evolving public explanations and scenarios would be proffered, even when they directly contradict previous ones. The lengths that folks would go to on TV, in the Twitter verse, and in everyday conversation to try to explain away any trace of culpability, irresponsibility, illegal activity, and guilt would be astounding.

The trouble is that when the goalposts keep shifting, some folks begin to subscribe to radically different preferences and make preposterous claims for the purpose of avoiding the pain of dissonance. How can the leader claim the documents are his and refuse to return them, and also suggest that they were planted at his residence? Operating under these kinds of double standards and tortured logic can lead to the erosion of basic principles and preferences once espoused, such as “the rule of law.” In other words, “no one is above the law, except in the case of when it’s my leader.” If that doesn’t sound fair, reasonable, or rational, that’s because it isn’t.

Many years ago, a colleague turned to me and asked, “Why do you assume people are going to be rational?” My colleague’s question looms large over today’s political events, settings and discourses.

When scenarios like the one described above move from the hypothetical to the real, I reflect upon how the planet I grew up on valued consistency, fairness, and common sense. (Those assumptions and expectations may require revising going forward). But for now, what is a less threatening way to shine a light on folks’ tectonic shifts in principles and preferences?

Humor might be an effective method of showing how absurd mental processes can become in service to alleviating cognitive dissonance (calling Trevor Noah). It might bring a few folks back from the brink of collapse of their once vaunted principles, the erosion of their starting values, and abandonment of their preferences in order to support a leader “no matter what.”

Because historically, cults of personality pose a threat to the form of government we used to prefer in droves, and a majority still does: A Constitutional republic with representative democracy and aspirations to the rule of law. To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin, that’s a good thing if you can keep it.