The neutral ground doesn’t belong to you.

Not because you got there first. Not because you drove in from Metairie with wooden stakes and caution tape. And not because you’ve been doing it for twenty years.

It’s public land. And what’s happening along St. Charles Avenue, Canal Street, and Carrollton Avenue isn’t tradition—it’s theft.

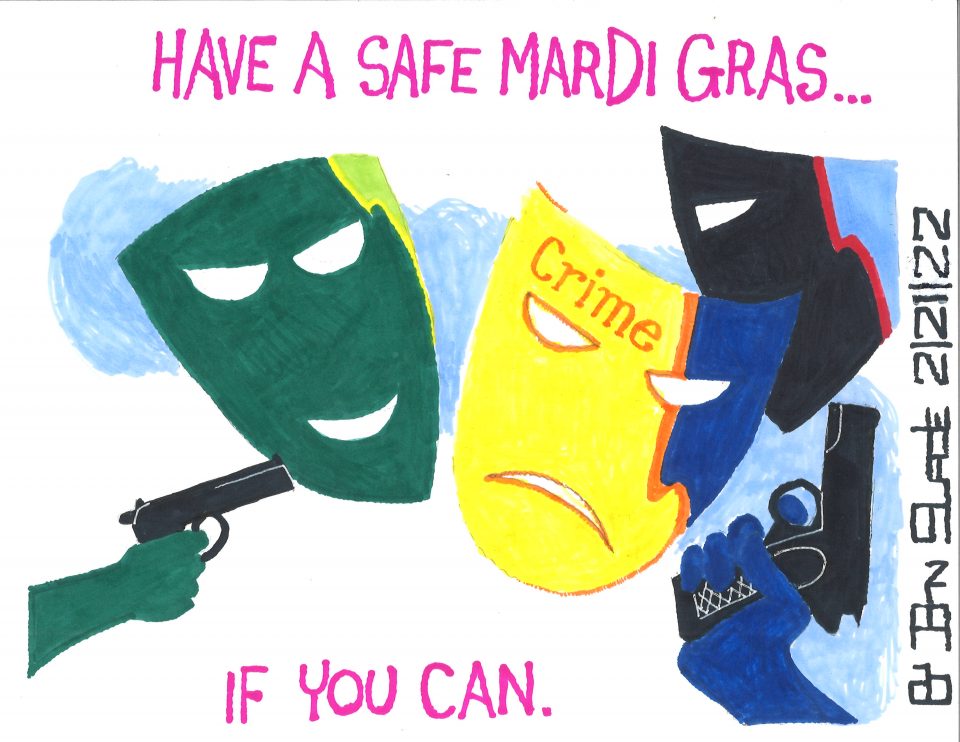

Days before the first parade rolls, the takeover begins. Wooden stakes pierce the grass. Yellow caution tape stretches across prime viewing spots like crime scene barriers. Spray paint marks rectangles on public property as if someone just bought a subdivision lot.

This isn’t happening four hours before showtime, as city law allows. It’s happening a full week in advance.

And every stake driven into that ground is illegal.

The Four-Hour Rule Everyone Ignores

New Orleans city ordinance is crystal clear: parade setup cannot begin more than four hours before start time.

That means no chairs. No tents. No stakes. Nope no tape. No spray-painted property lines on land you don’t own.

Yet enforcement remains spotty at best, invisible at worst. And when the law isn’t enforced, entitlement fills the vacuum.

The early claimers know this. They mark their territory days ahead, disappear, then return expecting everyone else to honor boundaries that were never legal in the first place.

Some get aggressive about it. Families report being told to move from open space. Residents get confronted for sitting on public grass. Arguments erupt over imaginary property lines that carry the weight of nothing except audacity.

This is what happens when illegal behavior gets normalized through neglect.

This Isn’t Just St. Charles Avenue

Most people think early staking is a St. Charles problem. That’s because St. Charles gets the attention—it’s the signature route, the postcard parade path where national media plants cameras and tourists clog the sidewalks.

But the problem extends far beyond Uptown.

Canal Street sees the same behavior. So does Carrollton during Endymion. Prime spots get marked off like reserved parking at a country club, days before anyone has legal right to claim them.

The pattern is consistent: mark early, leave, return later, defend aggressively.

And the people doing it? Many don’t even live here.

Outsiders Colonizing Public Space

Let’s be direct about what’s happening.

A significant portion of these early claimers live outside Orleans Parish. They chose homes in Jefferson Parish, St. Tammany, or further out. They don’t pay New Orleans property taxes. They don’t shoulder the infrastructure costs that city residents absorb year-round. And they don’t deal with the potholes, the water bills, the underfunded services.

But they drive in every Mardi Gras, stake out the best spots on public land, and act like landlords.

The word residents are using isn’t subtle: colonizing.

Historically, colonizers marked land and declared ownership over spaces that belonged to other people. The comparison isn’t accidental. New Orleans is a majority-Black city with a cultural legacy rooted in public celebration and communal space. Watching outsiders mark territory, police access, and intimidate residents carries uncomfortable historical weight.

This isn’t just about parade etiquette. It’s about who gets to control public space in a city they don’t even live in.

Mardi Gras Dies When It Gets Privatized

Mardi Gras works because it’s communal.

The magic isn’t in the floats or the beads—it’s in the shared experience. Strangers standing shoulder to shoulder. Kids darting through crowds. Neighbors gathering without fences or velvet ropes dividing them into access tiers.

The four-hour setup rule protects that spirit. It prevents organized groups from monopolizing prime real estate days in advance. It keeps the celebration democratic.

When people ignore the rule and enforce fake boundaries with aggression, they distort the culture. They turn public celebration into private territory. They replace communal joy with competitive hoarding.

That’s not tradition. That’s entitlement wearing tradition’s costume.

Leadership Spoke Up. Now Leadership Must Follow Through.

City Council member JP Morrell has correctly publicly called out early staking and criticized those breaking the rules. That matters. Leadership should name the problem clearly.

But messaging without enforcement is just noise.

The New Orleans Police Department is stretched dangerously thin, especially during Mardi Gras season. Staffing shortages are real. Proactive enforcement of staking violations competes with every other demand on limited resources.

But there’s infrastructure already in place that could help.

The Louisiana National Guard deploys during Mardi Gras. While Guard members don’t have arrest powers, they can patrol routes and report violations. Under city coordination, crews could remove illegal marking materials daily.

Imagine what happens when those stakes, that tape, those spray-painted lines disappear every single morning. The incentive to mark early vanishes. The behavior stops not because people develop sudden respect for the law, but because the effort becomes pointless.

Consistent removal changes behavior faster than any fine.

Related: Black Mardi Gras Traditions

The Solution Doesn’t Require New Laws

We don’t need another ordinance. We need enforcement of the one already on the books.

Here’s what consistent enforcement looks like:

Daily patrols along St. Charles, Canal, Carrollton, and every major route, clearing all unauthorized markings before dawn.

Public announcements declaring zero tolerance, issued well before parade season begins.

Fines for repeat offenders who keep testing the boundaries after being warned.

Visible action that signals the city is serious about protecting public space.

When illegal claims disappear every morning, the land-grab mentality collapses. People adapt. They show up four hours early like everyone else, or they find a different spot.

The solution is simple. What’s been missing is the will to implement it.

Protect the Public. Protect the Culture.

Public land belongs to the public. Not to the person who drove into town and spray painted the grass. Not to the group with the most aggressive territory defense. Certainly not to outsiders who drive in once a year and act like feudal lords.

Mardi Gras is not private property. It’s a cultural inheritance, and inheritance requires protection.

Every stake driven days early. Every stretch of caution tape blocking access. And every spray-painted line declaring fake ownership. They all chip away at what makes Mardi Gras matter.

The city must act before the first float rolls, not after conflicts have already erupted and someone’s viral video has made national news for all the wrong reasons.

Because here’s what’s at stake: the very nature of Mardi Gras as a public, communal celebration accessible to everyone.

Let the early claimers be disappointed. Let them complain on Facebook. Please let them threaten not to come back.

The neutral ground will survive without them.

The culture won’t survive if they keep treating it like conquered territory.

Final Word

Mardi Gras belongs to New Orleans.

Not to the person with the most stakes.

Not to the crew with the most tape.

To everyone. Equally. Without reservation systems or early access privileges.

The city knows the problem. Leadership has named it. Now it’s time to enforce the rules already written.

Because tradition isn’t about showing up first and defending your claim.

It’s about showing up together and sharing the celebration.

Key Takeaways:

- Early staking violates New Orleans’ four-hour setup ordinance

- Illegal territorial claims appear days or even a week before parades begin

- The practice extends beyond St. Charles to Canal Street and Carrollton Avenue

- Many early claimers live outside Orleans Parish but control city public space

- Residents describe the behavior as colonizing, with historical parallels

- City leadership has condemned the practice but enforcement remains inconsistent

- Daily removal of illegal markings would quickly eliminate the problem

- Protecting public access preserves Mardi Gras as a communal cultural celebration